Survey results reveal how Japanese perceptions of security in East Asia have changed following Russia's invasion of Ukraine.

The February 2022 Russian invasion of Ukraine underscored the clear threat that Russia poses to the existing international order. What actions would the United States, as the main defender of that existing international order, take in response to the crisis in Ukraine? What would the US response mean for the security of US allies, such as Japan? Indeed, the war in Ukraine seemed to remind many in Japan that similar elements of potential instability are also present in the security environment in East Asia.

This report compares two surveys on the views of Japanese citizens jointly conducted by the Japan Institute of International Affairs and the Chicago Council on Global Affairs in December 2021 and September 2022 and considers some of the ways in which public perceptions have changed between these two time periods with regard to the US-Japan alliance and Japan’s national security in general. In addition, we compare the findings of the September 2022 survey with the results of the annual 2022 Chicago Council Survey conducted July 15-August 1, 2022 among the American public, and consider the differences between American and Japanese perceptions of the alliance and national security.

Key Findings

-

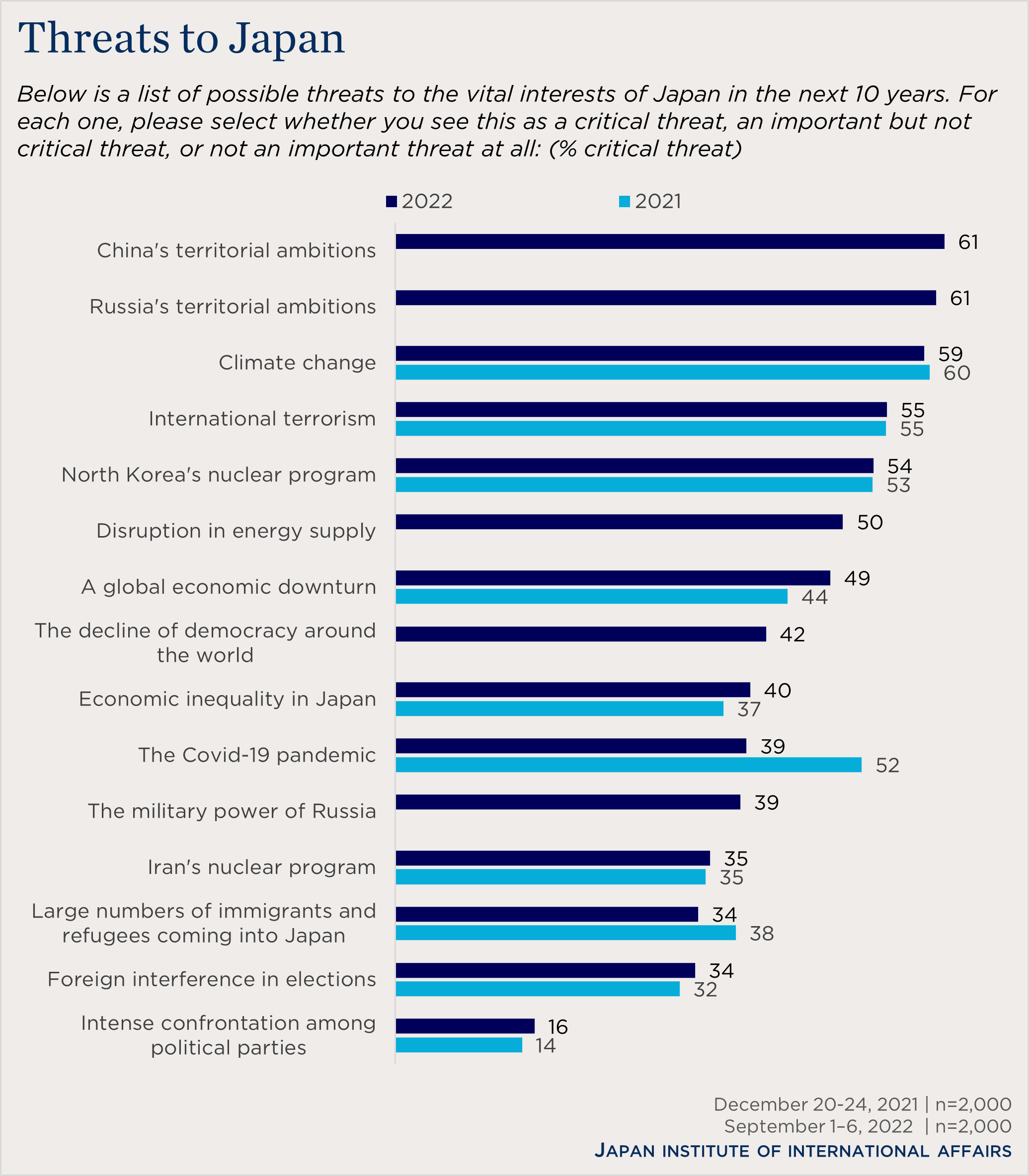

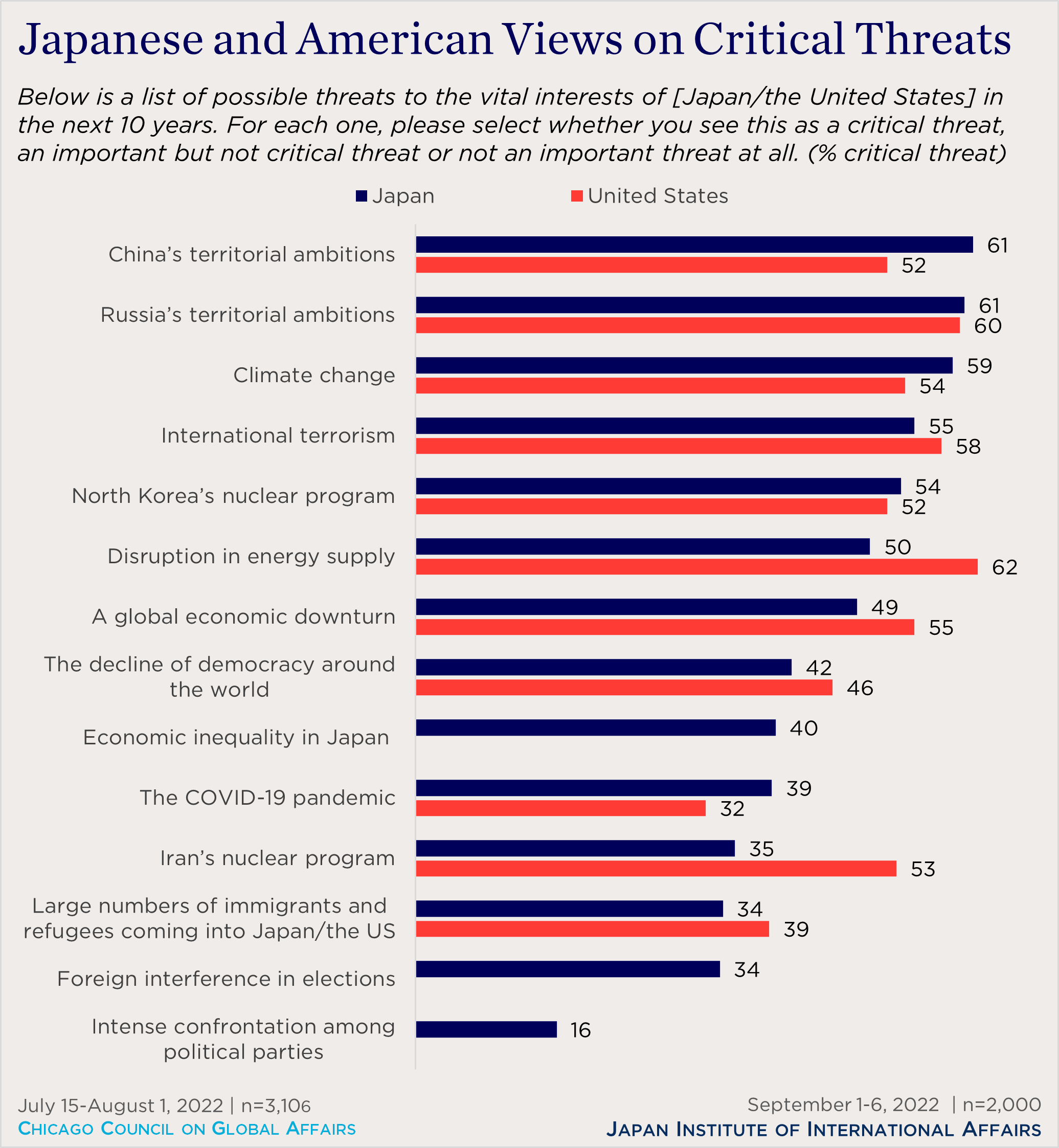

Majorities of Japanese view the territorial ambitions of Russia and China (61% each) as critical threats to Japan’s interests.

-

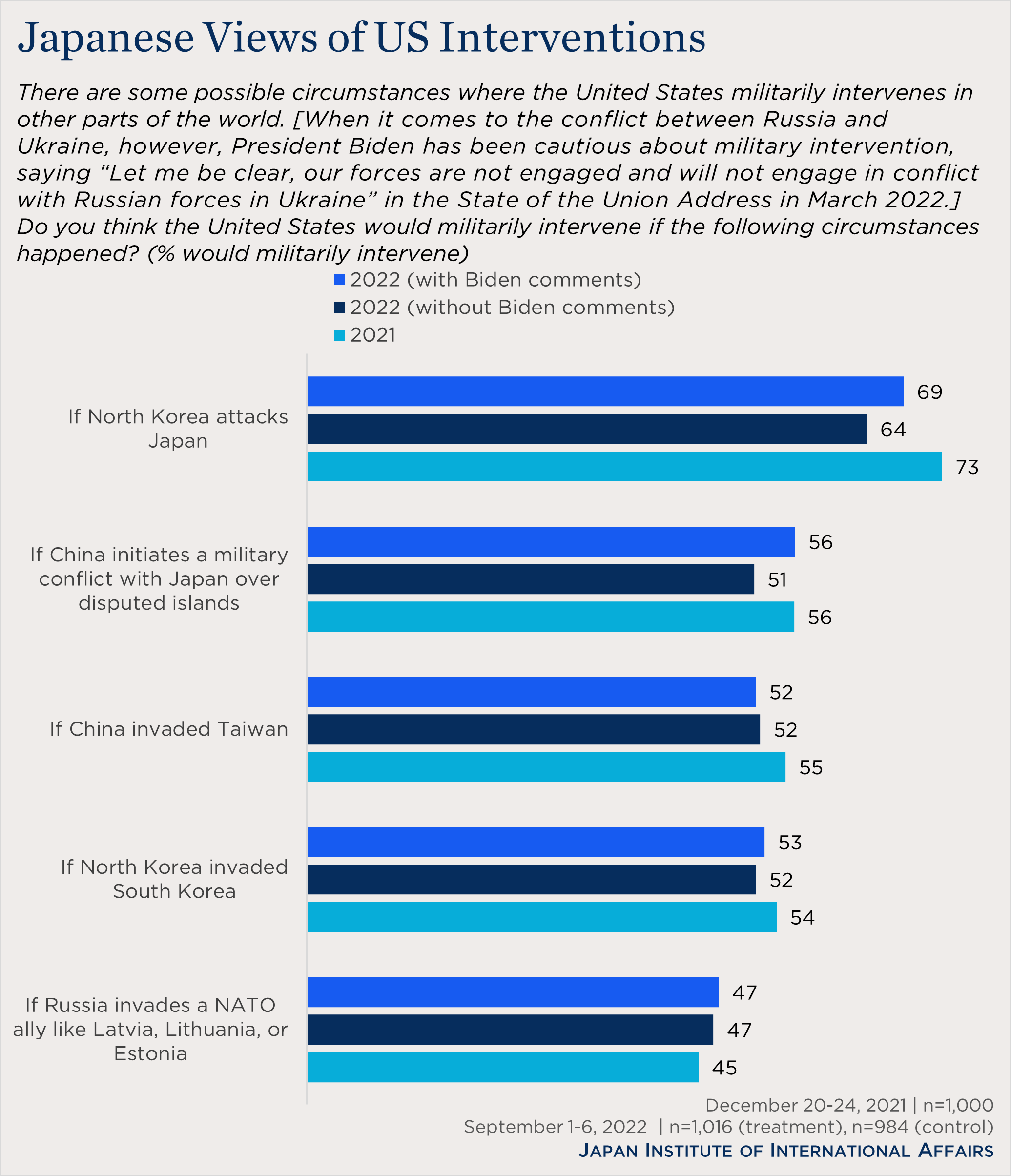

The Japanese public is less likely now to say that the United States would militarily intervene if Japan were attacked by North Korea (64%, down from 72%) or by China (51%, down from 55%).

-

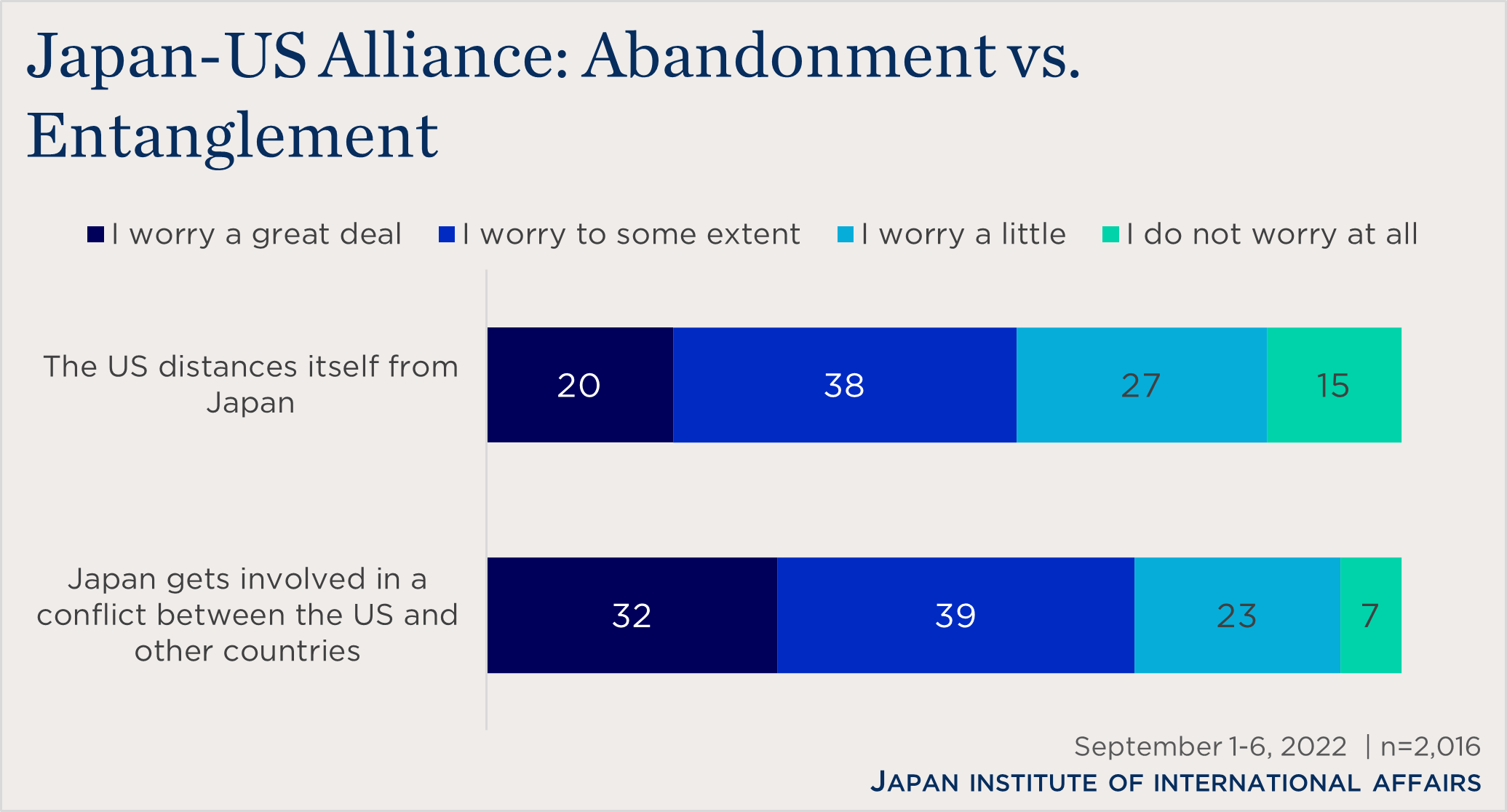

Though Japanese are concerned about both alliance abandonment and entanglement, they are more worried that Japan will get involved in a conflict between the US and other countries (71% worried, 32% worried a great deal) than about the US distancing itself from Japan (58% worried, 20% worried a great deal).

-

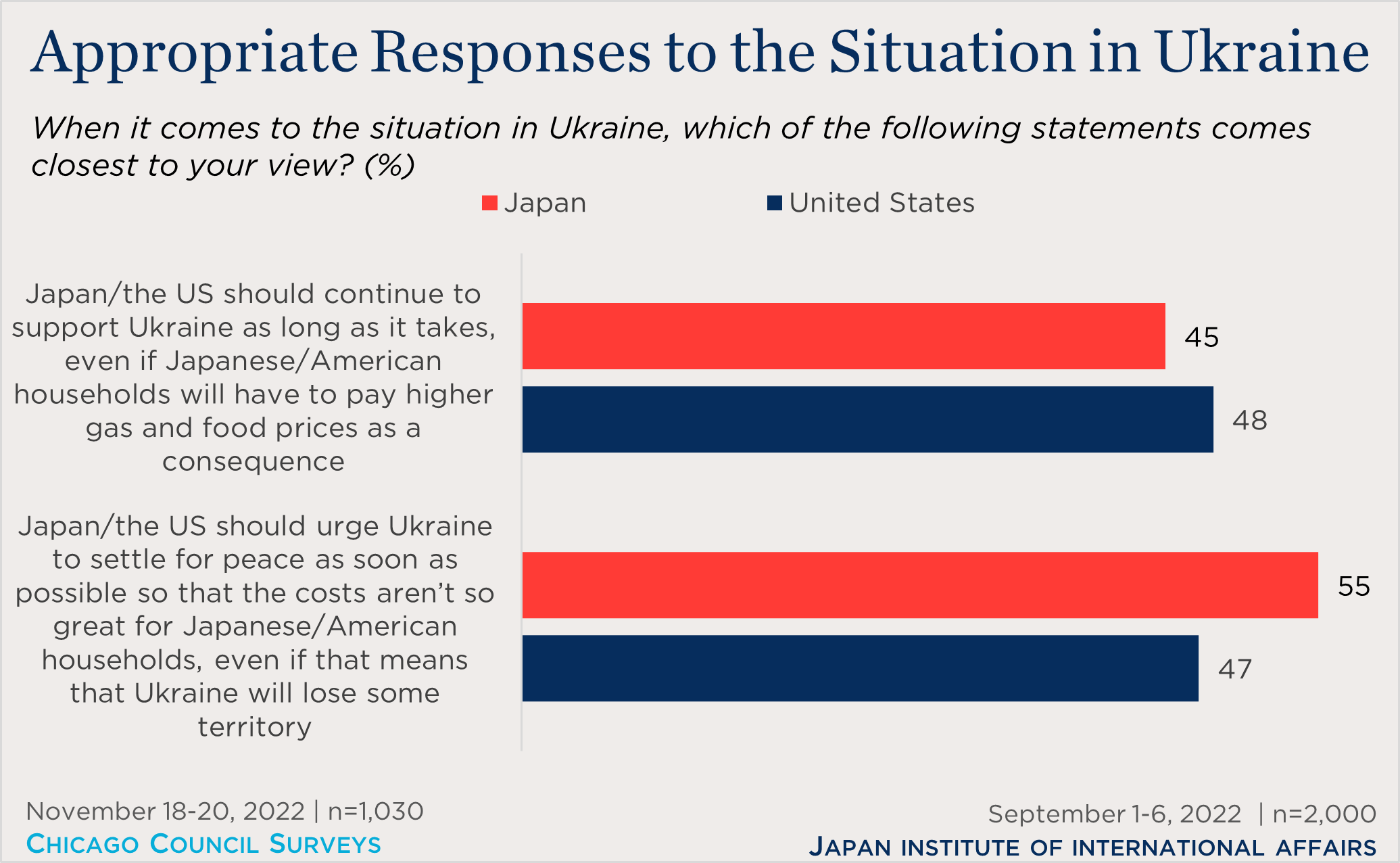

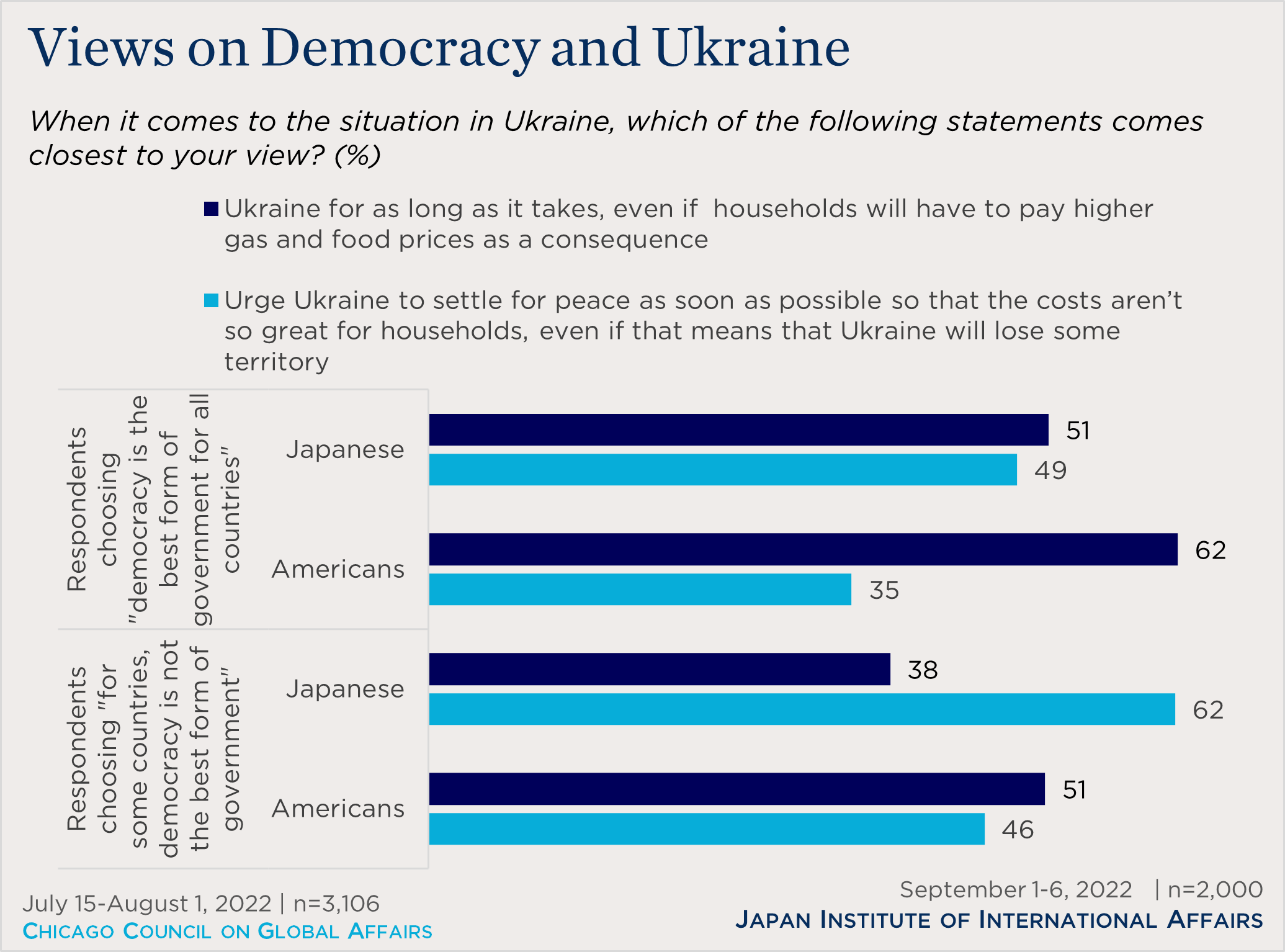

A majority of Japanese (55%) believe that Ukraine should be urged to settle for peace as soon as possible so that the costs aren’t as great for households in Japan, even if it means that Ukraine loses some territory. Americans are divided on the question: 48 percent are in favor of supporting Ukraine for as long as it takes, even at a greater cost to households in the United States, while 47 percent think Ukraine should accept territorial concessions to reduce costs to US households.

-

To better understand how America’s response to Ukraine has affected Japanese views of the US-Japan alliance, the survey included an experiment in which some respondents were given information about remarks by President Biden stipulating that the United States would not intervene militarily in Ukraine. Perhaps surprisingly, this group was more likely to think the United States would intervene militarily if North Korea invaded Japan or if the PRC initiated a military dispute with Japan over the Senkaku Islands a Chinese-initiated invasion of the Senkaku islands compared to respondents in the control group who did not receive this information.

Changing Perceptions of Security Threats

Russia’s invasion of Ukraine served as a shock to the international system, and to governments and publics around the world. Unlike in 2014, when Russia annexed Crimea, the international reaction has been swift and severe, with nations across the world joining together to punish Russia for the invasion and to support Ukraine. Japan has been no exception: with public support, Japan has joined with other G7 nations to sanction Moscow and has provided significant economic and humanitarian aid to Kiev. The shock of Russia’s invasion is also clearly reflected in the Japanese public’s strong concerns about Russia’s territorial ambitions. Today, six in 10 Japanese (61%) see Russian ambitions as a critical threat to Japan. In December 2021, just months before the war, only four in 10 Japanese (39%) saw Russian military power as a critical threat to their country.

A similarly large percentage of Japanese view China’s territorial ambitions as a critical threat (61%). This is similar to the percentage of respondents in the 2021 survey who viewed the development of China as a world power as a critical threat to Japan (55%). With Russian and Chinese territorial ambitions leading the list of perceived threats to Japan, it seems reasonable to conclude that the invasion of Ukraine has led to a sense among people in Japan that Russia and China pose a threat to the country’s national security.

In addition, there was a slight increase in the percentage of Japanese who identified a global economic downturn as a critical threat (49%, up from 44%), reflecting growing concerns about the outlook for the global economy. Conversely, the percentage of Japanese who saw the COVID-19 pandemic as a critical threat fell significantly during this period (39%, down from 52%). That decline suggests that anxiety about the pandemic is easing following the widespread adoption of vaccines and the slow relaxation of COVID-related restrictions. And as in 2021, Japanese continue to regard climate change as a more significant threat than North Korea’s nuclear program or international terrorism.

Levels of Trust in US Commitment to the Alliance

Following the Russian invasion of Ukraine, much speculation has focused on the extent to which the United States would involve itself in the conflict. Of course, Ukraine is not an official US ally, but it is likely that the actions and behavior of the United States will be seen by Japan and other allies as indicative of the strength of US commitment to its partners and alliances.

Survey results suggest that the Japanese public does indeed view the United States’ focus on the war in Ukraine as decreasing the probability of American intervention in Asian conflicts. Over the past year, the proportion of Japanese citizens who believe that the United States would intervene militarily declined, either in the event of a North Korean attack on Japan (64%, down from 72%) or if China started a military conflict with Japan over the Senkaku Islands (51%, down from 55%). By contrast, there was no significant change in the perceived likelihood of US intervention for any of the other postulated scenarios.

In addition, the survey included an experiment in which respondents were randomly divided into two groups. One of these (the treatment group) was given information about President Biden’s statement in his March 2022 State of the Union address that US armed forces “are not engaged and will not engage in the conflict with Russian forces in Ukraine.” Respondents were then asked whether they thought the United States would intervene militarily in each of the above-described hypothetical situations. The results showed that for the two situations of North Korean attack on Japan and Chinese-initiated conflict with Japan over the Senkaku Islands, the treatment group was more likely than the control group who had not been primed with information about President Biden’s remarks to believe that the United States would intervene militarily—by five percentage points, respectively.

This suggests that President Biden’s explicit statement that the United States would not directly intervene militarily in the crisis in Ukraine had the converse effect of making Japanese citizens feel more confident in US commitment to its alliance with Japan. Although there is only a limited amount that can be concluded on this subject from this survey alone, one possibility is that the knowledge that the United States would not devote military resources to Ukraine made Japanese respondents feel more confident that the United States would honor its commitments in East Asia. Moreover, Biden’s refusal to send US forces to the aid of a non-allied nation could reinforce the view that the United States only intervenes on behalf of official allies, meaning the Japanese public could feel secure given their official alliance status (and the administration’s frequent emphases of the importance of the US-Japan alliance). Again, in this experiment, Biden’s remarks had no effect on any of the other hypothetical scenarios other than those of a Chinese or North Korean attack on Japan.

Fear of Abandonment vs. Fear of Entrapment

In any alliance, two conflicting feelings inevitably coexist: a fear of being abandoned, and a fear of getting unwillingly entangled involved in a conflict. There is always a worry that an ally might fail to come to the aid when a country is attacked by an adversary. But if the country attempts to deepen the relationship with its ally to assuage this fear, it may increase the risk of being dragged into a conflict between the ally and other countries.

According to the results of the September 2022 survey, the percentage of respondents who said they worried a great deal that Japan might “get involved in a conflict between the US and other countries” (32%) was higher than the percentage who said they worried a great deal that the US might “distance itself from Japan” (20%). This suggests that for Japanese citizens, the fear of getting dragged into a third-party conflict is stronger than the fear of being abandoned.

Role of the Self-Defense Forces

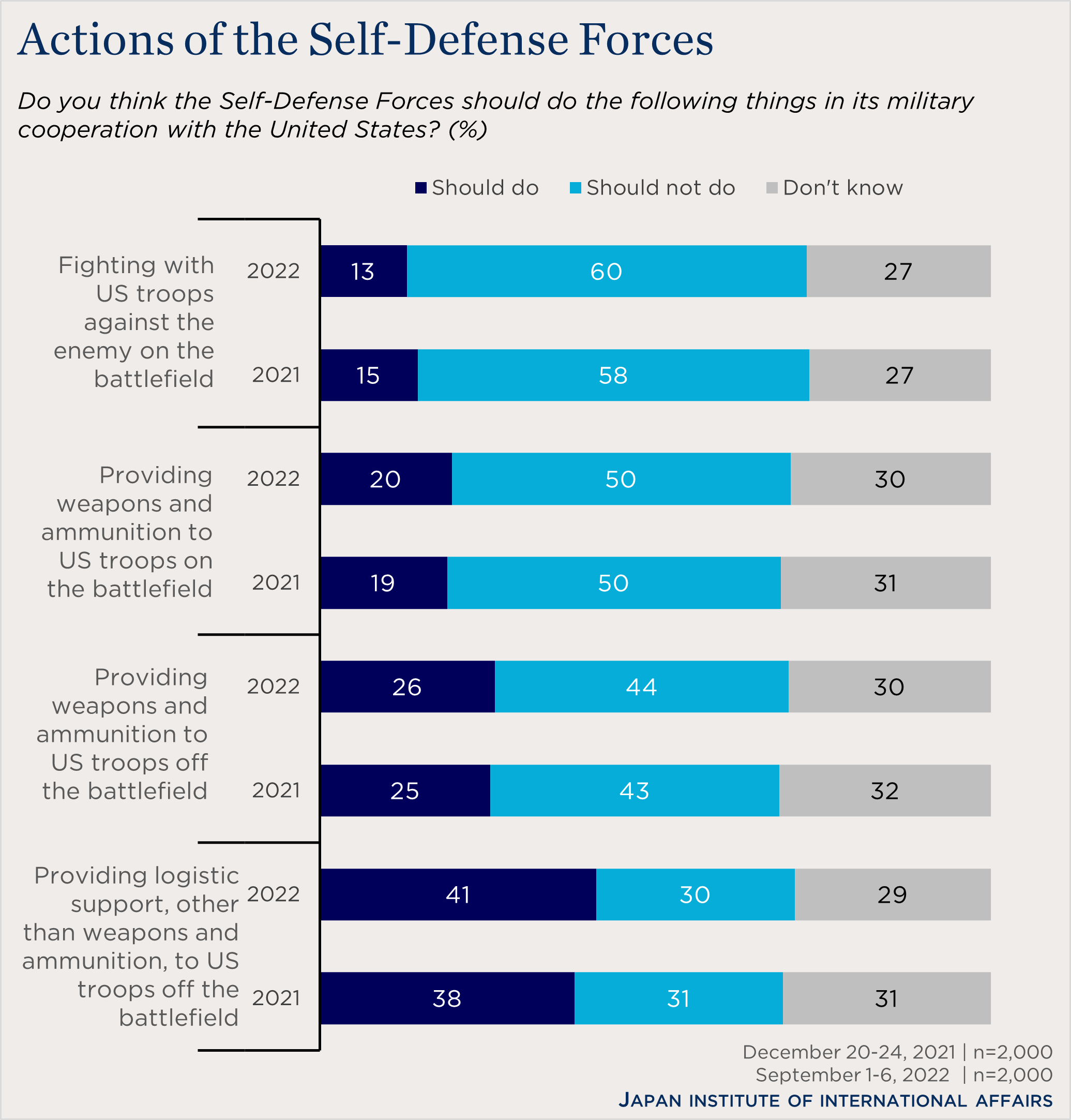

The fact that the Russian invasion of Ukraine has dented the confidence of some Japanese citizens in US commitment to its alliance with Japan raises the possibility that some Japanese people might also have changed their minds about the desirable extent of Japan’s contribution to the alliance. This fear of abandonment could push the public to work more closely with the United States in order to persuade the US of the value of the alliance and guard against any potential abandonment. However, few Japanese want the country to increase its military contribution to the US-Japan alliance: 17 percent, up only slightly from 2021 (13%). A majority prefer instead to maintain the present level of military commitment (54%).

Moreover, the Japanese public remains opposed to a range of potential roles for the Self-Defense Forces in cooperation with the US military. Despite the public’s concerns about abandonment, a comparison of the results for the December 2021 and September 2022 surveys shows no significant increase in the percentage of respondents who answered that the Self-Defense Forces should cooperate with the United States by “fighting with US troops against the enemy on the battlefield,” which is not permitted under the current laws. There was also no significant change in the percentage who said that Japan should or should not cooperate by “providing weapons and ammunition to US troops off the battlefield,” which is already possible under current laws. Even the form of cooperation that poses the smallest hurdles, namely “providing logistic support, other than weapons and ammunition, to US troops off the battlefield,” was supported by less than a majority of respondents, underlining just how eager the Japanese citizens are to avoid being dragged into a conflict.

Perceived Global Influence of Various Countries

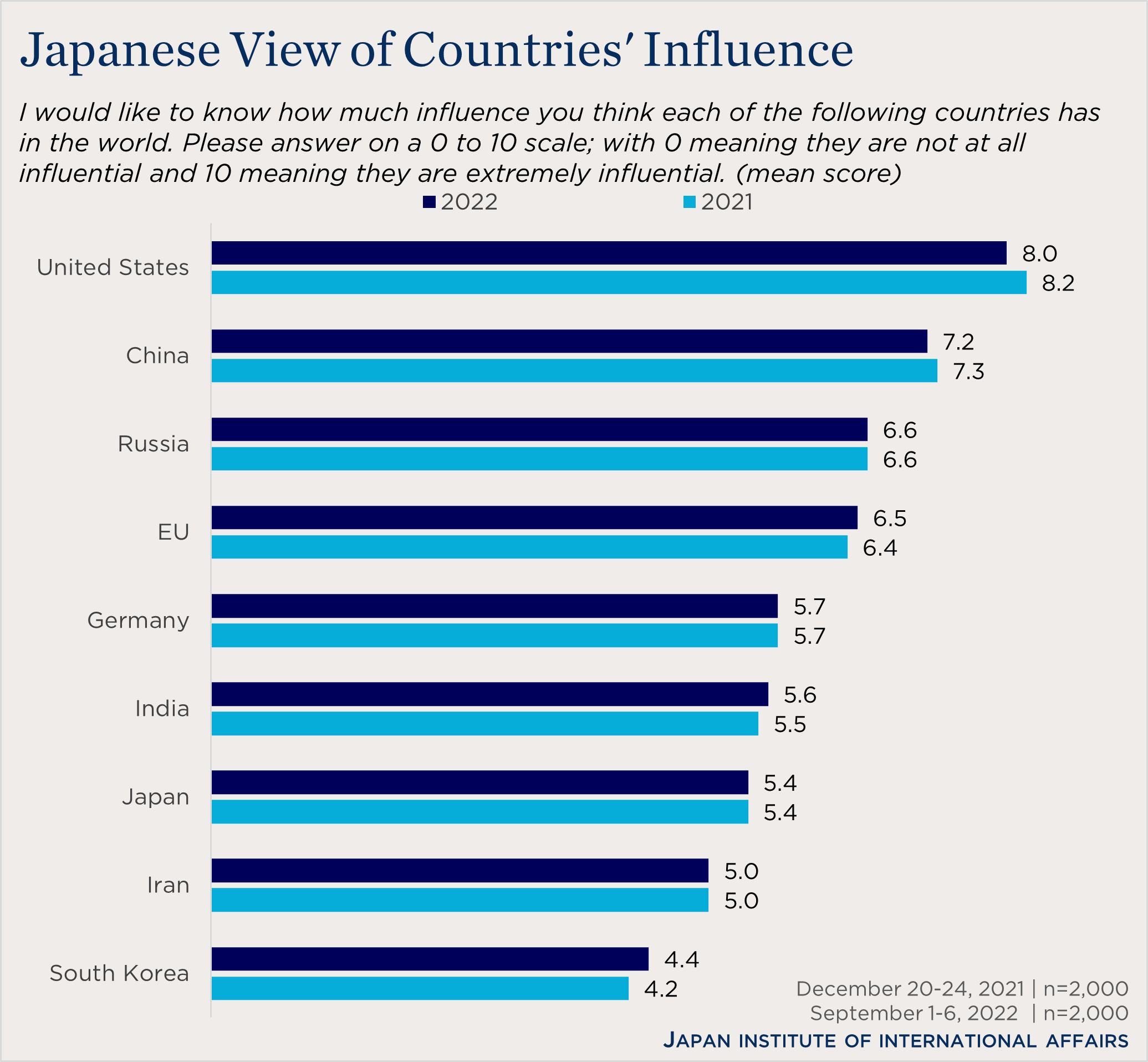

The Russian invasion of Ukraine came as a major shock for the international community and consequently may have influenced Japanese citizens’ views on the alliance with the United States and national security. This gives rise to the possibility that it may also have led Japanese citizens to have a higher estimate of Russia’s international influence. In fact, however, a comparison of responses in the 2021 and 2022 surveys to questions that asked respondents to rate the global influence of various countries on a 10-point scale, the average score for Russia’s perceived global influence was 6.6 in both surveys, showing no change in absolute terms. There was also no difference in the perception of Russia’s relative influence compared to other countries. This is true not only for Russia, but for the perceived influence of all countries, including the United States. Essentially, despite the shock of the Russian invasion of Ukraine, it is fair to say that Japanese citizens so far see no significant change in the international balance of power, partly perhaps because of widespread media reports of the difficulties Russian troops have encountered since the war began.

Japanese and American Views on Support for Ukraine

So far, this report has examined changes in the attitudes of Japanese citizens between the 2021 and 2022 Japan surveys, based on responses to questions in these surveys about the Japan-US alliance and national security. The following section instead compares the findings of the 2021 Japan survey with those of a survey conducted among Americans by the Chicago Council on Global Affairs in July and August 2022.

First, the answers to questions about possible responses to the situation in Ukraine indicate that both Japanese and Americans are concerned about the costs of supporting Ukraine indefinitely. A majority (55%) of Japanese citizens agreed with the statement that Japan should urge Ukraine to settle for peace as soon as possible so that the costs aren’t so great for Japanese households, even if that means that Ukraine loses some territory. On the other side, a sizeable minority of Japanese (45%) say that Japan should continue to support Ukraine as long as it takes, even if Japanese households have to pay higher gas and food prices as a consequence.

Americans, too, are concerned about these costs. The most recent Chicago Council polling, from November 2022, finds that Americans are divided on this question. Half (48%) say that their country should support Ukraine for as long as it takes, even at cost to US households, while a similar proportion (47%) prefer Ukraine to settle for peace in order to reduce costs for American households. This is a shift from July 2022, when a majority of Americans (58%) thought the United States should support Ukraine for as long as it takes, regardless of costs to American households.

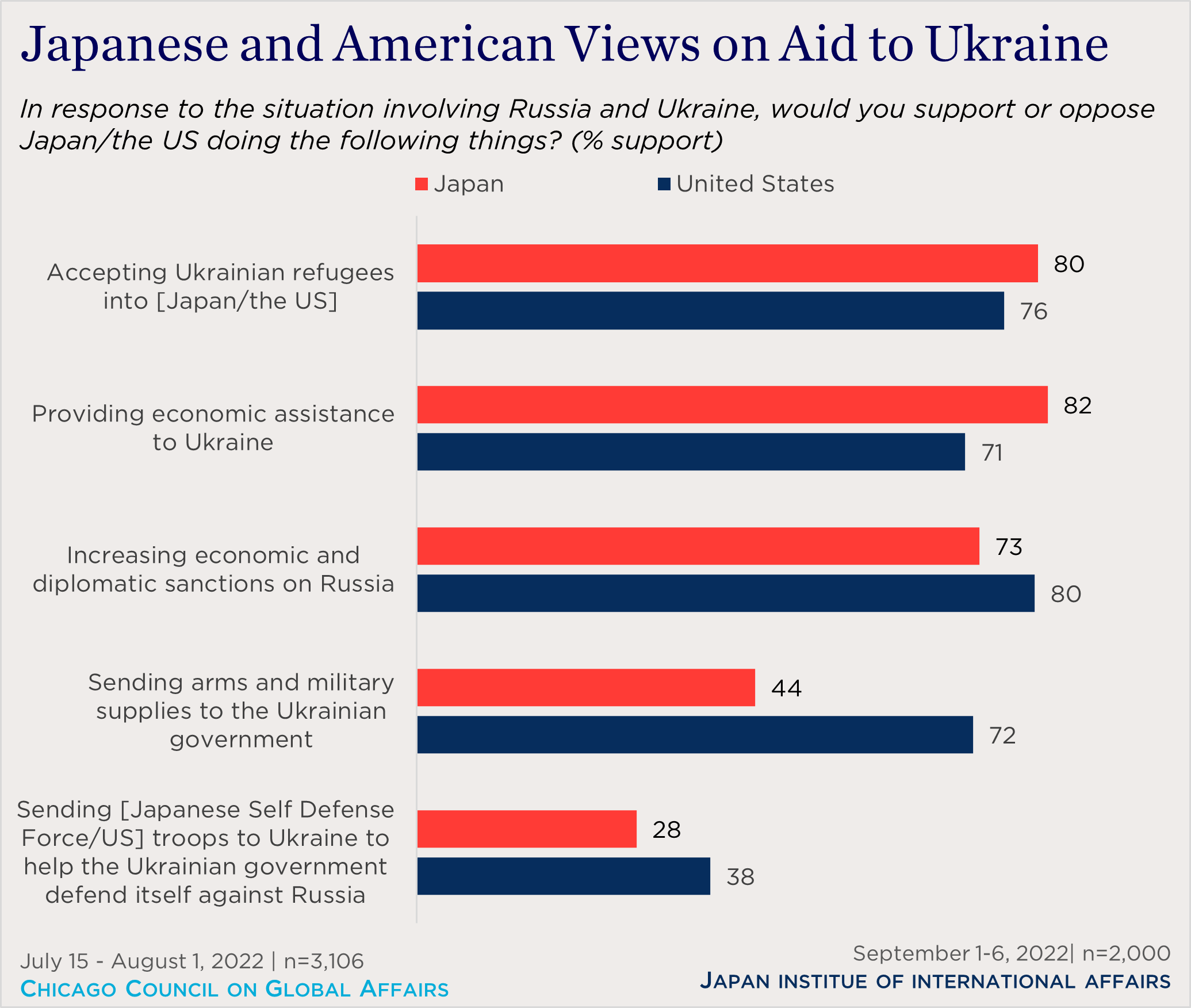

This doesn’t mean that the Japanese public is unsupportive of Ukraine. In fact, Japanese respondents show higher levels of support than Americans for the idea of accepting Ukrainian refugees and providing economic assistance to Ukraine, and three-quarters of Japanese support increased economic and diplomatic sanctions on Russia. However, they are less far likely than Americans to support measures entailing greater risks and costs, such as sending arms and military supplies to the Ukrainian government, and like most Americans, a majority oppose direct military intervention.

Numerous possible explanations could be put forward for these different Japanese and American views on aid to Ukraine. For one, while the Japanese government has been aligned with other G7 nations in imposing economic sanctions on Russia, Japan’s aid to Ukraine has been heavily weighted toward economic and humanitarian assistance, while the United States has done far more to provide arms and military supplies to Kiev.

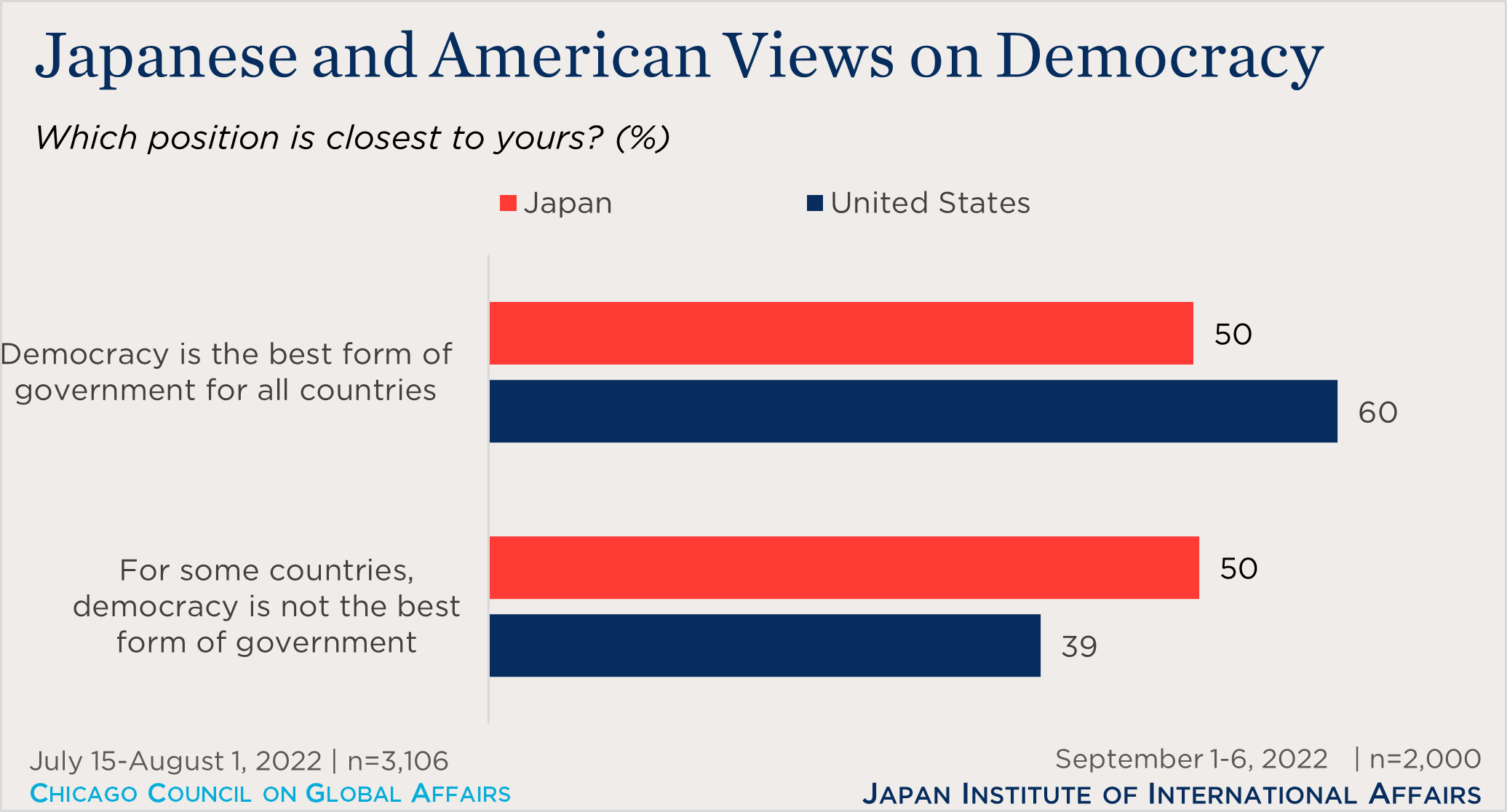

Another factor that may play a role is the difference between Japanese and Americans in terms of their beliefs about the universality of democracy. Six in 10 Americans (60%) believe that democracy is the best political system for all countries, while four in 10 (39%) say that for some countries, democracy is not the best political system. Japanese are more divided on the question, with half (50%) taking each side of the argument, suggesting that Japanese are less convinced of the universality of democracy than their American counterparts.

As deeper analysis shows, in both Japan and the United States, beliefs about the universality of democracy are reflected in views about how long to support Ukraine. When respondents are divided into two groups according to these two views on the universality of democracy, those who believe democracy is the best system for all countries are more likely to favor supporting Ukraine for as long as it takes, even at cost to their own nation. Conversely, those who believe some countries are not suited for democracy are more likely to say that Ukraine should sue for peace in order to decrease costs on their own nations’ households. This may be because people who believe that democracy is a universal value are more likely to see the war in Ukraine within the framework of a struggle between democratic and authoritarian states. As citizens of a democratic state themselves, such people may regard this struggle as one that involves them personally, making them more prepared to make sacrifices to defend democracy.

Differences in Threat Perceptions between Japan and the United States

Finally, looking at the different perceptions of threats in Japan and the United States following the Russian invasion of Ukraine shows that Americans and Japanese generally share the same threat perceptions—but with some notable differences.

Concerns about Russia are a unifying feature: a similar six in 10 Japanese (61%) and Americans (60%) assessed Russia's territorial ambitions as a critical threat. However, there is more of a difference when it comes to China's territorial ambitions. While six in 10 Japanese (61%) describe this as a critical threat, topping their list of concerns, just over half of Americans say the same (52%), and it ranks far lower for the American public (7th out of 11 potential threats). This suggests that although Japanese and American citizens share a similar perception of the threat posed by Russia’s growing military influence as represented by its invasion of Ukraine, they do not perceive the threat posed by China’s expanding military influence, particularly in East Asia, in quite the same way.

There are also several issues where Americans are more concerned than are Japanese, particularly Iran’s nuclear program. A majority of Americans (53%) see this as a critical threat, while only a third of Japanese (35%) say the same. Interestingly, Americans (62%) are also more concerned than are Japanese (50%) about a disruption in energy supply, despite the two nations’ notably different reliance on international energy markets.

Conclusion

What implications can we draw from the results of the foregoing analysis? First, we can say that respondents in Japan have a perception of current international issues that is accurate to a considerable degree, reflected in their increasing perception of Russia as a threat and the dangers of a global economic downturn, while their perceptions of the threat posed by the COVID-19 pandemic have faded as the pandemic has started to ease.

At the same time, however, the Japanese public does not believe that their country should engage proactively with every international issue of concern. They tend to take the view that as a country with critical threats very close to their own borders, the scope within which Japan can engage with international problems is limited, particularly in military terms.

There are understandable reasons for why the Japanese public would be reluctant to engage on international security issues. the fact that Japan is itself confronted with acute security challenges—including China, North Korea, and Russia—provides an incentive for Japan to focus its efforts closer to home.

Additionally, even if Japan does not contribute proactively to security within the international community, the United States will likely make protecting Japan a priority. And despite some concerns among the Japanese people that the US may not come to their aid in a crisis, the public is less fearful of being abandoned by the United States than of becoming involved in conflicts between the United States and other countries. This may be one reason why the Japanese public is so hesitant to commit the Self-Defense Forces to even non-combat supporting roles for its US ally.

This is not to say that the Japanese public has turned on the alliance with the United States. Far from it. Even today, at a time when commentators have been pointing to the decline of US power for many years, the Japanese public continues to see the United States as the most influential nation in the world and their preferred leading nation on the world stage.

It also seems that Japan does not fully share the stronger concerns held in the United States on issues such as Iran’s nuclear program, potential disruptions to the global energy supply, and the defense of democracy. These differences could arise from the public’s “one-nation pacifism” position, but it is tempting to conclude that people in leadership positions in Japanese politics and public discourse are not doing enough to communicate foreign policy issues to Japanese citizens.

This is a particularly acute problem today. More than in previous decades, it is vitally important for the Japanese public to understand that at a time when the US-Japan alliance is playing a more critical role for US foreign policy, expectations for Japan to take on a greater burden—and greater risk—are higher than they have been in the past. We suggest there is a need for Japanese citizens and their political leaders to use the ongoing turmoil in the international community that has been triggered by the Russian invasion of Ukraine as an opportunity to reconsider the state of Japanese national security founded on the alliance with the United States.

Japan data comes from a survey conducted by the Nippon Research Center (NRC) for the Japan Institute of International Affairs. The survey was conducted online September 1–6, 2022, among a sample of 2,000 Japanese citizens 18 and older drawn from the NRC research panel and using age, gender, region, and city-size quota groups. The margin of sampling error for the full sample is +/- 2.22 percentage points and is higher for subgroups or partial-sample items. For the purposes of this analysis, the results were weighted for age, gender, and education level using the 2020 Population Census. Data from the December 2021 survey has also now been weighted to the results of the 2020 Population Census, and as a result, some values in this report differ from those in the original report on the 2021 survey (“Strong Partners: Japanese and US Perceptions of America and the World”).

Most US data comes from the 2022 Chicago Council Survey of the American public on foreign policy, a project of the Lester Crown Center on US Foreign Policy. The 2022 Chicago Council Survey was conducted July 15–August 1, 2022, by Ipsos using its large-scale nationwide online research panel, KnowledgePanel, in both English and Spanish among a weighted national sample of 3,106 adults 18 or older living in all 50 US states and the District of Columbia. The margin of sampling error for the full sample is +/- 1.8 percentage points. The margin of error is higher for partisan subgroups or for partial-sample items. The 2022 Chicago Council Survey was made possible by the generous support of the Crown family and the Korea Foundation.

Additional US data comes from a November 18-20, 2022 survey conducted for the Chicago Council on Global Affairs by Ipsos using its large-scale nationwide online research panel, KnowledgePanel. This survey was conducted in English among a weighted national sample of 1,030 adults 18 or older living in all 50 US states and the District of Columbia. The margin of sampling error for the full sample is +/- 3.0 percentage points. This survey was made possible by the generous support of the Carnegie Corporation of New York.

Related Content

Public Opinion

Public Opinion

American public opinion toward Japan has never been warmer, Council data show.

Defense and Security

Defense and Security

What are the implications of Japan’s largest military buildup since World War II, and what does this mean for the US-Japan security alliance?

Public Opinion

Public Opinion

While the American public is hesitant to get involved in a conflict between China and Japan, Americans across party lines want to build strong relations with US allies in Asia.