The Council came to life in 1922 in a Chicago dominated by isolationism. It led the great debate over American participation in World War II and, after that war, over the nation’s new dominant role in the world. As a forum, it struggled with all the major issues—Vietnam, the Cold War, the War on Terrorism, and whether America is best served by an active or restrained foreign policy.

The following draws from Longworth’s book on 100 years of the Chicago Council on Global Affairs, reflecting on these key periods of a tumultuous history, one full of ups and downs, driven by vivid characters, and enlivened by constant debate over where both the institution and its city belong in the world.

1922-1944 Isolationism and the Great Debate

When the Council was founded in 1922, it was a worldly outpost in a city and a Midwest dominated by isolationism. Soon, it would stand at the center of the great debate about American participation in World War II.

The early 1920s was a turbulent time. Post-Versailles resentments were already building toward the next war. Tsarist Russia had become communist. Benito Mussolini has just turned Italy fascist. Hyperinflation wracked Germany. Mahatma Gandhi pressed for Indian independence. Chicago, resolutely mid-continental, stood aloof, geographically and intellectually, from this turmoil.

Rowing against this tide, a small group of internationally-minded Chicagoans established the Council—then called the Chicago Council on Foreign Relations—"to promote general public interest in the foreign policy of the United States" by bringing in expert speakers to lecture on the events of the world. At its birth, the Council was an alliance between North Shore grandees and the international experts of the University of Chicago. By the 1930s, this remote and elitist approach gave way to the great debate over American participation in the coming war.

Speakers During This Time

In the 1930s, the Council's programs drew thousands of people to hear from interventionists, isolationists, and even outright Nazis. Its radio broadcasts also brought the debate about American involvement in World War II to hundreds of thousands of listeners around the Midwest.

On November 28, 1922, former Prime Minister of France Georges Clemenceau speaks to a Council audience of 5,000 in Chicago's Auditorium Theater.

In 1929, the Council becomes the center of debate on whether America should aid European allies. Speakers include former President Herbert Hoover (pictured), Edward R. Murrow, and Jan Mazaryk.

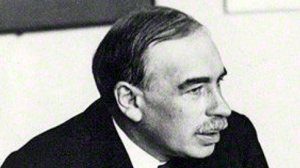

In 1931, the British economist John Maynard Keynes speaks to the Council on the war debts and reparations imposed on Germany at Versailles.

Edgar Ansel Mowrer, the Daily News correspondent, gives the first report to the Council on the war in the Pacific in 1941.

Behind the scenes, Council leaders led the campaign in the Midwest to give aid to European allies. When the war came, the region sent its leaders to Washington and its sons to fight and turned its industry into the arsenal that won the victory. For this, the Council could take a bow.

The intelligent thing for us to do is to inform ourselves as accurately as possible. The purpose of the Chicago Council on Foreign Relations is not only to stimulate interest in these questions but to provide reliable information, and the opportunity for unprejudiced discussion of them.

Adlai E. Stevenson,

Council president from 1935 to 1937

Adlai E. Stevenson,

Council president from 1935 to 1937

Play Video

Play Video

Continue exploring this era

1922

The Council is founded by a group of 23 men and women. Jacob M. Dickinson becomes the first president (chair equivalent today), and Polly Root Collier becomes the first executive secretary (president equivalent).

The Council holds its first public meeting, featuring George Wickersham, a founding member of the New York Council and the attorney general in the Taft Administration.

1923

Lord Robert Cecil, who would go on to win the Nobel Peace Prize, speaks to a crowd of 2,500 people at a Council program.

Jane Addams, who is best known in Chicago as the founder of Hull House, speaks to the Council on "Impressions of Political Movements in the Orient."

1924

The Council's offices move to the Marquette Building, now the home of the John D. and Catherine T. MacArthur Foundation.

1925

The Council launches the monthly newsletter News Bulletin, later called Foreign Notes, meant to both inform members who couldn’t attend meetings and to make up for the lack of in-depth foreign news in Chicago newspapers.

1926

W.E.B. Dubois becomes the first African American to speak on the Council's stage. He speaks on the benefits of increased cooperation with like-minded people in Europe and other countries.

After Polly Collier returns to Europe, her assistant Isabella McLaughlin Stephens becomes executive secretary.

1929

The Council's membership reaches 1,500.

Journalist Clifton Utley becomes editor of Foreign Notes. He doubles the pages from two to four and writes most of the copy himself.

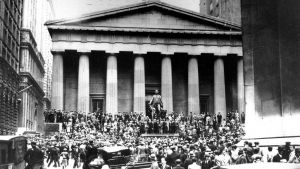

The Wall Street stock market crashes and a global depression would soon ensue.

1931

Clifton Utley, who was only 26 years old at the time, becomes executive secretary of the Council.

1933

Former German Foreign Minister Richard von Kuhlmann speaks to the Council on Adolf Hitler.

Nazi sympathizer Friedrich Schönemann speaks to the Council. A week later, he gave the same speech in Boston and incited a riot that involved 5,000 Bostonians and police.

1935

The Council's membership returns to a pre-Crash level of 2,050. Membership would continue to increase annually throughout this decade.

Adlai E. Stevenson II, the grandson of US vice president Adlai Stevenson I, becomes Council president. At 33 years old, he was the youngest president in the Council's history.

1938

Radio station WAAF broadcasts the Council's programs to 200,000 listeners across the Midwest. Soon WAAF would broadcast all Council meetings, usually at 1 pm after a classical concert.

Radio correspondent Edward R. Murrow and Jan Masaryk—the son of the founder of Czechoslovakia—speak at Council programs on the aftermath of the Munich conference.

1940

Clifton Utley and Adlai Stevenson become Chicago leaders of the campaign urging US intervention in war. Through its programs, its members, and its broadcasts, the entire Council played a leading role in preparing the Midwest for America's eventual participation in the coming war.

1941

Japanese attack the US fleet at Pearl Harbor, and America officially enters World War II.

The Council issued a statement recalling that it was founded after World War I, and now devoted itself to helping win the second world war.

1942

The Council's former president Adlai E. Stevenson, now special assistant to Navy Secretary, speaks to the Council on war aims.

Louise Leonard Wright becomes executive secretary, likely becoming the first woman to hold such a role at a world affairs organization. Wright was formerly the national chairman of the foreign policy committee of the League of Women Voters.

Council offices move to the John Crerar Library Building along with the Pan-American Council, the League of Nations Association, the National Film Board of Canada, the International Relations Library, and the American Scandinavian Foundation—forming what became known as the International Relations Center.

1943

Speakers, including Adlai E. Stevenson and Jan Masaryk, speak at Council programs on the need for a US postwar alliance for peace.

1944

Edgar Ansel Mowrer returns to the Council to speak on D-Day, the allied invasion of Normandy during World War II.

Explore full timeline

1922

-

February 20 -

The Council is founded by a group of 23 men and women. Jacob M. Dickinson becomes the first president (chair equivalent today), and Polly Root Collier becomes the first executive secretary (president equivalent).

-

March 18 -

The Council holds its first public meeting, featuring George Wickersham, a founding member of the New York Council and the attorney general in the Taft Administration.

1923

-

April 16 -

Lord Robert Cecil, who would go on to win the Nobel Peace Prize, speaks to a crowd of 2,500 people at a Council program.

-

Jane Addams, who is best known in Chicago as the founder of Hull House, speaks to the Council on "Impressions of Political Movements in the Orient."

1924

-

The Council's offices move to the Marquette Building, now the home of the John D. and Catherine T. MacArthur Foundation.

1925

-

April 19 -

The Council launches the monthly newsletter News Bulletin, later called Foreign Notes, meant to both inform members who couldn’t attend meetings and to make up for the lack of in-depth foreign news in Chicago newspapers.

1926

-

W.E.B. Dubois becomes the first African American to speak on the Council's stage. He speaks on the benefits of increased cooperation with like-minded people in Europe and other countries.

-

After Polly Collier returns to Europe, her assistant Isabella McLaughlin Stephens becomes executive secretary.

1929

-

The Council's membership reaches 1,500.

-

Journalist Clifton Utley becomes editor of Foreign Notes. He doubles the pages from two to four and writes most of the copy himself.

-

October 29 -

The Wall Street stock market crashes and a global depression would soon ensue.

1931

-

Clifton Utley, who was only 26 years old at the time, becomes executive secretary of the Council.

1933

-

Former German Foreign Minister Richard von Kuhlmann speaks to the Council on Adolf Hitler.

-

Nazi sympathizer Friedrich Schönemann speaks to the Council. A week later, he gave the same speech in Boston and incited a riot that involved 5,000 Bostonians and police.

1935

-

The Council's membership returns to a pre-Crash level of 2,050. Membership would continue to increase annually throughout this decade.

-

Adlai E. Stevenson II, the grandson of US vice president Adlai Stevenson I, becomes Council president. At 33 years old, he was the youngest president in the Council's history.

1938

-

Radio station WAAF broadcasts the Council's programs to 200,000 listeners across the Midwest. Soon WAAF would broadcast all Council meetings, usually at 1 pm after a classical concert.

-

Radio correspondent Edward R. Murrow and Jan Masaryk—the son of the founder of Czechoslovakia—speak at Council programs on the aftermath of the Munich conference.

1940

-

Clifton Utley and Adlai Stevenson become Chicago leaders of the campaign urging US intervention in war. Through its programs, its members, and its broadcasts, the entire Council played a leading role in preparing the Midwest for America's eventual participation in the coming war.

1941

-

December 7 -

Japanese attack the US fleet at Pearl Harbor, and America officially enters World War II.

-

December 16 -

The Council issued a statement recalling that it was founded after World War I, and now devoted itself to helping win the second world war.

1942

-

The Council's former president Adlai E. Stevenson, now special assistant to Navy Secretary, speaks to the Council on war aims.

-

Louise Leonard Wright becomes executive secretary, likely becoming the first woman to hold such a role at a world affairs organization. Wright was formerly the national chairman of the foreign policy committee of the League of Women Voters.

-

Council offices move to the John Crerar Library Building along with the Pan-American Council, the League of Nations Association, the National Film Board of Canada, the International Relations Library, and the American Scandinavian Foundation—forming what became known as the International Relations Center.

1943

-

Speakers, including Adlai E. Stevenson and Jan Masaryk, speak at Council programs on the need for a US postwar alliance for peace.

1944

-

Edgar Ansel Mowrer returns to the Council to speak on D-Day, the allied invasion of Normandy during World War II.

1945-1955 A New Postwar World

The end of World War II presented the world with one of history's great blank slates. The Council focused on how, not whether, the United States should lead in building this new postwar world.

With the end of World War II the atomic age began, but no one knew how to survive it. Much of Europe and Asia lay in ruins. The Communists moved to control China. The Soviet Union, so recently an ally, loomed as a lethal foe. The United States was the only intact world power but was deeply divided on how to use that power.

Council leaders, especially its former president Adlai Stevenson, helped create the United Nations. Outposts of isolationism remained, led by the Council’s perennial sparring partner, the Chicago Tribune, but the Council aimed to help shape a new postwar world.

Speakers During This Time

As the Kremlin took control of half of Europe, Council speakers proclaimed the dawn of the Cold War and debated America’s new policy of containment. Secretary of State George Marshall came to explain why his Marshall Plan was vital to America’s own security. Indian Premier Jawaharlal Nehru said the great driving force in Asia was nationalism. Eleanor Roosevelt called for a foreign policy based on human rights.

US Secretary of State Edward Stettinius speaks to the Council in 1945 on the upcoming San Francisco conference forming the United Nations.

Former First Lady Eleanor Roosevelt speaks to the Council in 1947 on international human rights. She's pictured here, right, with Louise Wright, the Council's executive secretary.

Abba Eban speaks to the Council in 1949. Eban would soon become Israel's first ambassador to the United Nations.

Pearl Buck, the American novelist who won the Nobel Prize for Literature for her novels about China, speaks to the Council in 1951.

Abroad, Russia became a nuclear power, and the long slog of the Cold War set in. The Korean War, the first inconclusive war, ended in a stalemate. At home, isolationism gave way to a new view of the United States as the defender of the free world, a sort of global policeman, with an indiscriminate foreign policy that would lead to involvement in a faraway place called Vietnam.

The debate between the isolationists, so-called, and the internationalists, so-called, is now, I think it is fair to say—even in Chicago—completed. Our new basic commitments abroad have received the overwhelming ratification of the Congress and they have the support of the people.

Columnist Walter Lippmann,

speaking to the Council in 1952

Columnist Walter Lippmann,

speaking to the Council in 1952

Continue exploring this era

1945

Combat stops, and World War II ends, five years after it began.

The Council absorbs the Speakers Bureau, which had been founded by the League of Nations Association in the late 1930s and was run by the International Relations Center through the war.

Melvin Brorby, one of Chicago's leaders in advertising, joined the Council's executive committee and later became its president.

1947

Young Men's group, which was composed of young professionals and businessmen sponsored by an executive committee member, was formed. Members of the group were invited to special luncheon meetings.

The Council launches a program series with the University of Chicago. The series kicked off with seven lectures on France, followed by a series on American foreign policy the next year.

US Secretary of State George Marshall gives a nationally broadcast speech at the Council about the controversial Marshall Plan.

1948

Council office moves to 116 S. Michigan Avenue, its home for nearly 40 years. The United World Federalists and the Chicago Horticultural Society also moved with it.

The Council teams up with the State Department to sponsor an "Institute on United States Foreign Policy," a two-day session bringing together one hundred public opinion leaders from across the Midwest.

1950

The Korean War begins. UN Secretary General Trygve Lie speaks to the Council on the war, noting the response to North Korea’s invasion of South Korea showed that the precedent of Korea will not be forgotten.

The Chicago Tribune accuses the Council of starting the Korean War. Council members, it said, "oughtn’t to be looking for somebody else to blame for the disaster in Korea when they themselves did what they could to bring it about."

Owen Lattimore—an author and Asia expert, whom Senator Joseph McCarthy called "the top Russian espionage agent in the United States"—speaks to the Council on McCarthyism.

1952

John Foster Dulles speaks to the Council, opposing the US policy of containment of the Soviet Union.

Once again, former First Lady Eleanor Roosevelt speaks to the Council—this time on the topic of Asia.

The Red Squad, a notorious but secretive branch of the Chicago Police Department that spied on suspected communists and other dissidents and subversives, begins surveillance of the Council.

Porter McKeever becomes Council executive secretary. McKeever was a former campaign aide for Adlai Stevenson and the director of information for the US delegation to the United Nations.

The Council's staff was growing, and the move from the Crerar Building had raised the rent. So, the Council begins special funding drives and creates a corporate sponsorship program to broaden its financial base.

1953

Carter Davidson, a journalist and much-admired former foreign correspondent with the Associated Press, becomes Council executive secretary.

The Council begins holding programs outside of Chicago, cooperating with the University of Chicago for "World Politics" programs in eight North Shore suburbs.

1954

The Council sponsors an International Holiday Ball in Chicago's Aragon Ballroom, with an all-nations orchestra and an international floor show.

1955

Carter Davidson launches the World Spotlight program on WTTW, the Chicago educational television channel, which reached 110,000 viewers each week. At the same time, the Council produces a series of radio programs on the Chicago stations WMAQ and WLS, reaching an estimated audience of 200,000.

Explore full timeline

1945

-

August 15 -

Combat stops, and World War II ends, five years after it began.

-

The Council absorbs the Speakers Bureau, which had been founded by the League of Nations Association in the late 1930s and was run by the International Relations Center through the war.

-

Melvin Brorby, one of Chicago's leaders in advertising, joined the Council's executive committee and later became its president.

1947

-

Young Men's group, which was composed of young professionals and businessmen sponsored by an executive committee member, was formed. Members of the group were invited to special luncheon meetings.

-

The Council launches a program series with the University of Chicago. The series kicked off with seven lectures on France, followed by a series on American foreign policy the next year.

-

US Secretary of State George Marshall gives a nationally broadcast speech at the Council about the controversial Marshall Plan.

1948

-

Council office moves to 116 S. Michigan Avenue, its home for nearly 40 years. The United World Federalists and the Chicago Horticultural Society also moved with it.

-

The Council teams up with the State Department to sponsor an "Institute on United States Foreign Policy," a two-day session bringing together one hundred public opinion leaders from across the Midwest.

1950

-

The Korean War begins. UN Secretary General Trygve Lie speaks to the Council on the war, noting the response to North Korea’s invasion of South Korea showed that the precedent of Korea will not be forgotten.

-

The Chicago Tribune accuses the Council of starting the Korean War. Council members, it said, "oughtn’t to be looking for somebody else to blame for the disaster in Korea when they themselves did what they could to bring it about."

-

Owen Lattimore—an author and Asia expert, whom Senator Joseph McCarthy called "the top Russian espionage agent in the United States"—speaks to the Council on McCarthyism.

1952

-

John Foster Dulles speaks to the Council, opposing the US policy of containment of the Soviet Union.

-

Once again, former First Lady Eleanor Roosevelt speaks to the Council—this time on the topic of Asia.

-

The Red Squad, a notorious but secretive branch of the Chicago Police Department that spied on suspected communists and other dissidents and subversives, begins surveillance of the Council.

-

Porter McKeever becomes Council executive secretary. McKeever was a former campaign aide for Adlai Stevenson and the director of information for the US delegation to the United Nations.

-

The Council's staff was growing, and the move from the Crerar Building had raised the rent. So, the Council begins special funding drives and creates a corporate sponsorship program to broaden its financial base.

1953

-

Carter Davidson, a journalist and much-admired former foreign correspondent with the Associated Press, becomes Council executive secretary.

-

The Council begins holding programs outside of Chicago, cooperating with the University of Chicago for "World Politics" programs in eight North Shore suburbs.

1954

-

The Council sponsors an International Holiday Ball in Chicago's Aragon Ballroom, with an all-nations orchestra and an international floor show.

1955

-

Carter Davidson launches the World Spotlight program on WTTW, the Chicago educational television channel, which reached 110,000 viewers each week. At the same time, the Council produces a series of radio programs on the Chicago stations WMAQ and WLS, reaching an estimated audience of 200,000.

1956-1975 Vietnam

The Vietnam War dominated world diplomacy, domestic politics, the streets of America, and the tenor of the Council itself. In the summer of 1968, the debate over the war exploded at the Democratic national convention right at the Council's front door.

Since World War II, Americans had swung from isolationism to a messianic self-image that led to Vietnam. At the start, Council speakers defended the war, but soon, they were questioning whether even the mighty United States had limits that must be obeyed. By 1966, seven years before the war ended, in a poll at a Council meeting, more than 2,000 members opposed US policy in Vietnam and overwhelmingly called for negotiations to end the war.

Speakers During This Time

Some speakers addressing Vietnam said the domino theory demanded an American victory. Others called the war "illegal, immoral, un-American, un-winnable." Two leading political scientists, the interventionist Zbigniew Brzezinski and the realist Hans Morgenthau, staged a titanic debate on America's proper place in the world.

Two of the nation’s leading political scientists, Hans Morgenthau of the University of Chicago (pictured above) and Zbigniew Brzezinski of Columbia University, came together in 1965 for a debate at the Council.

Under-Secretary of State George Ball (left), with Council members Richard Thomas and Herman Smith in 1972, was an early opponent of the Vietnam War.

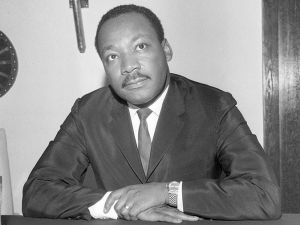

While the Council brought the world to Chicago during this period, it ignored the crisis in race relations that disfigured the city itself. The assassination of Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. in 1968 ignited rage and rioting in cities across the nation. Some of the worst violence took place in Chicago, which still bears the scars fifty years later, but the Council literally paid no attention. In the months after, it held no programs on racial issues, sponsored no studies, convened no panels, and made no attempt to link the crisis to the nation’s image abroad.

It never entered anybody's mind. We didn’t have a sense of the Council as a place that could reach out to domestic issues, even if they impacted foreign affairs.

Later, as the Vietnam war wound down, the mood of a chastened nation shifted to restraint, so much so that the Council found it necessary to hold programs on neo-isolationism. The new watchword became not isolationism but interdependence.

Continue exploring this era

1958

When Soviet Ambassador Mikhail Menshikov speaks to the Council, he is met by protestors—from mostly Baltic and East European nations—as he leaves.

At a Council program in the Palmer House, Kwame Nkrumah, the prime minister of newly independent Ghana, makes headlines by accusing John Foster Dulles of causing the Suez crisis two years earlier.

1959

The Council faces a financial crisis. Payroll is slashed by one-third, total spending is cut by 20 percent, and deficits force a major staff cut.

The Council invites Fidel Castro, the Cuban guerilla leader who marched his troops into Havana and seized power, to speak at a program. There is no record of him responding to the invite.

1960

Edmond Eger becomes Council executive secretary. Within four years, he tripled the Council's membership and quadrupled its net worth.

1961

The Council begins its charter flight program for members, giving them steep discounts on flights to Europe. Annual income quickly passed $100,000 for the first time and kept climbing.

The Council brings Edward R. Murrow and eight CBS foreign correspondents to Chicago for a panel discussion on global problems and trouble spots.

The Council forms the Chicago Committee, with 220 charter members, made up of the city's senior and most influential business leaders. David M. Kennedy, the CEO of Continental Illinois Bank and a future treasury secretary in the Nixon Administration, is named the first chairman.

1962

The Council celebrates its 40th anniversary by commissioning a history of its first four decades from a University of Chicago graduate student named Kenneth T. Jackson, who goes on to become one of the nation's most distinguished historians.

Former executive director Carter Davidson gives likely the first speech the Council heard on the Vietnam War, predicting a US victory.

1965

Garrick Utley gives a Council speech that questions US policy in Vietnam.

The Council's programming on WTTW resumes.

1966

Poll of the Council's audiences shows majority oppose US policy in Vietnam.

1967

Council begins hiring staff with professional foreign policy experience.

1968

Alex Seith, a very ambitious young lawyer, is elected president of the Council board of directors at the age of 34.

The Democratic National Convention roils Chicago.

1969

The Council launches Young Ambassadors program, sending inner-city teens to Europe.

1970

French President Georges Pompidou arrives to speak at the Council and is met by 10,000 pro-Israeli demonstrators. France had just sold 110 Mirage jets to Muammar Gaddafi's Libya and not yet officially acknowledged the role its government played in the Holocaust.

Helmut Kohl, the minister president, or governor, of the German province of Rhineland-Palatinate—and future chancellor of Germany—spoke at the Council's Atlantic Conference.

1971

Council membership hits a high of 22,000.

John E. Rielly, who previously worked for the Democratic Vice President Hubert Humphrey, becomes Council executive secretary.

The Council begins sponsoring Atlantic Conferences, and later, Ditchley Conferences.

1972

The Council marks its 50th anniversary.

The Council begins a program series on neo-isolationism.

1974

The Council bylaws are rewritten. The Executive Committee becomes the Council's board of directors, led by a chair of the board. John Rielly, the executive secretary, becomes Council president.

1975

The Council's signature poll, "American Public Opinion and US Foreign Policy," is launched.

Explore full timeline

1958

-

When Soviet Ambassador Mikhail Menshikov speaks to the Council, he is met by protestors—from mostly Baltic and East European nations—as he leaves.

-

At a Council program in the Palmer House, Kwame Nkrumah, the prime minister of newly independent Ghana, makes headlines by accusing John Foster Dulles of causing the Suez crisis two years earlier.

1959

-

The Council faces a financial crisis. Payroll is slashed by one-third, total spending is cut by 20 percent, and deficits force a major staff cut.

-

The Council invites Fidel Castro, the Cuban guerilla leader who marched his troops into Havana and seized power, to speak at a program. There is no record of him responding to the invite.

1960

-

Edmond Eger becomes Council executive secretary. Within four years, he tripled the Council's membership and quadrupled its net worth.

1961

-

The Council begins its charter flight program for members, giving them steep discounts on flights to Europe. Annual income quickly passed $100,000 for the first time and kept climbing.

-

The Council brings Edward R. Murrow and eight CBS foreign correspondents to Chicago for a panel discussion on global problems and trouble spots.

-

The Council forms the Chicago Committee, with 220 charter members, made up of the city's senior and most influential business leaders. David M. Kennedy, the CEO of Continental Illinois Bank and a future treasury secretary in the Nixon Administration, is named the first chairman.

1962

-

The Council celebrates its 40th anniversary by commissioning a history of its first four decades from a University of Chicago graduate student named Kenneth T. Jackson, who goes on to become one of the nation's most distinguished historians.

-

Former executive director Carter Davidson gives likely the first speech the Council heard on the Vietnam War, predicting a US victory.

1965

-

Garrick Utley gives a Council speech that questions US policy in Vietnam.

-

The Council's programming on WTTW resumes.

1966

-

Poll of the Council's audiences shows majority oppose US policy in Vietnam.

1967

-

Council begins hiring staff with professional foreign policy experience.

1968

-

Alex Seith, a very ambitious young lawyer, is elected president of the Council board of directors at the age of 34.

-

The Democratic National Convention roils Chicago.

1969

-

The Council launches Young Ambassadors program, sending inner-city teens to Europe.

1970

-

French President Georges Pompidou arrives to speak at the Council and is met by 10,000 pro-Israeli demonstrators. France had just sold 110 Mirage jets to Muammar Gaddafi's Libya and not yet officially acknowledged the role its government played in the Holocaust.

-

Helmut Kohl, the minister president, or governor, of the German province of Rhineland-Palatinate—and future chancellor of Germany—spoke at the Council's Atlantic Conference.

1971

-

Council membership hits a high of 22,000.

-

John E. Rielly, who previously worked for the Democratic Vice President Hubert Humphrey, becomes Council executive secretary.

-

The Council begins sponsoring Atlantic Conferences, and later, Ditchley Conferences.

1972

-

The Council marks its 50th anniversary.

-

The Council begins a program series on neo-isolationism.

1974

-

The Council bylaws are rewritten. The Executive Committee becomes the Council's board of directors, led by a chair of the board. John Rielly, the executive secretary, becomes Council president.

1975

-

February 15 -

The Council's signature poll, "American Public Opinion and US Foreign Policy," is launched.

1976-1995 End of the Cold War

Council speakers began speculating whether, after 40 Cold War years, the Soviet threat might finally be crumbling. Economic issues—oil, trade, the new power of multinational corporations—replaced military rivalries on the spearpoint of American diplomacy.

For the first time since the end of World War II, the United States faced a clean slate. The Cold War was over and the Soviet Union was gone, not only vanquished but vanished. The United States ruled as the sole hegemon. Capitalism and liberal democracy had won.

After World War II, the United States created a structure that guided policy for 40 years. Now, it tried to do the same but, lacking a single foe, dithered. The Council, too, struggled to find a place. The Cold War had been the focus of all it had done; now, there were many issues but no central theme.

Speakers during this time

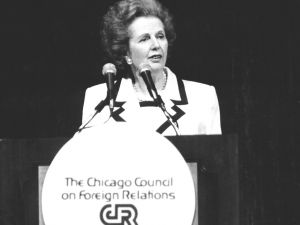

Titans—Mikhail Gorbachev, Boris Yeltsin, Helmut Kohl, Margaret Thatcher, Henry Kissinger—crossed the Council stage as the Cold War came to a close. Colin Powell argued that “the obligation of leadership is ours.” But how to use it? Speakers on the Council's stage worried that instant communications—"the CNN effect"—distorted any well-planned foreign policies.

Henry Kissinger, who served as Secretary of State under Presidents Richard Nixon and Gerald Ford, speaks to Council audiences often, including in 1976.

Jimmy Carter, then the governor of Georgia and presidential candidate, appears on the Council's stage in 1976.

In 1980, presidential candidate Ronald Reagan lays out a “grand strategy” from the Council's stage.

George H.W. Bush, who became Reagan's vice president, breaks the candidates’ general silence on the Iranian crisis in 1980.

Boris Yeltsin (second from right), the future president of Russia, speaks to the Council in 1989.

Play Video

Play Video

Former Prime Minister Margaret Thatcher speaks to the Council in 1991.

Play Video

Play Video

Former Soviet President Mikhail Gorbachev speaks to the Council in 1992.

It was a busy decade, what with the Yugoslav wars, Somalia, Rwanda, the rise of China, and, mostly, the arrival of globalization. Chicago itself had changed. Once a brawny but isolated industrial powerhouse, it had become a global city, a hub of globalization, with a different role in the world. To thrive, it needed to understand this role and it was up to the Council to lead this thinking.

Play Video

Play Video

The Chicago Council on Foreign Relations stands at the center of the foreign policy debate in Chicago. It has done the most to make Chicagoans global-minded, but it still has a great deal left to do.

Continue exploring this era

1976

Gerald Ford, the only sitting president to appear on the Council stage in Chicago, speaks at the Palmer House.

1977

Henry Kissinger films a special NBC television broadcast, where he answers questions from a Council audience.

1978

The John D. and Catherine T. MacArthur Foundation opens in Chicago. By 1981, the foundation gives its first grant to the Council and becomes an important source of funding going forward.

1982

Secretary of State Alexander Haig speaks to the Council at its sixtieth-anniversary dinner. During this speech, Haig tells the Council he's dispatching top aides to the Middle East to try to settle three problems there: the Iran-Iraq War, autonomy for Palestinians, and the civil war in Lebanon.

1986

Program speakers visiting the Council begin to debate the possible breakup of the Soviet Union.

Helmut Kohl returns to the Council to give two speeches—one to business leaders on trade relations, and the other on changing East-West relations after the Reykjavik summit between Gorbachev and President Reagan.

1987

The Council begins managing and operating the Chicago World Trade Conference. The first keynote speaker is Alan Greenspan; a few weeks later, Greenspan was named president of the Federal Reserve Bank.

In an attempt to draw in younger members, the Council launches its Young Professionals program. It provided lectures on current events but also opportunities for networking through parties and trips.

1988

The Council receives a $3 million grant from the German Konrad Adenauer Foundation for European Policy Studies, to be paid out over ten years.

1990

Helmut Schmidt, the former chancellor of West Germany, speaks at the Council.

1992

The current US Secretary of Defense Dick Cheney speaks at the Council. He would go on to be the 46th vice president of the United States.

1995

Robert McNamara, the former defense secretary and master planner of the Vietnam War, speaks to the Council on mistakes of the war.

Explore full timeline

1976

-

Gerald Ford, the only sitting president to appear on the Council stage in Chicago, speaks at the Palmer House.

1977

-

Henry Kissinger films a special NBC television broadcast, where he answers questions from a Council audience.

1978

-

The John D. and Catherine T. MacArthur Foundation opens in Chicago. By 1981, the foundation gives its first grant to the Council and becomes an important source of funding going forward.

1982

-

Secretary of State Alexander Haig speaks to the Council at its sixtieth-anniversary dinner. During this speech, Haig tells the Council he's dispatching top aides to the Middle East to try to settle three problems there: the Iran-Iraq War, autonomy for Palestinians, and the civil war in Lebanon.

1986

-

Program speakers visiting the Council begin to debate the possible breakup of the Soviet Union.

-

Helmut Kohl returns to the Council to give two speeches—one to business leaders on trade relations, and the other on changing East-West relations after the Reykjavik summit between Gorbachev and President Reagan.

1987

-

The Council begins managing and operating the Chicago World Trade Conference. The first keynote speaker is Alan Greenspan; a few weeks later, Greenspan was named president of the Federal Reserve Bank.

-

In an attempt to draw in younger members, the Council launches its Young Professionals program. It provided lectures on current events but also opportunities for networking through parties and trips.

1988

-

The Council receives a $3 million grant from the German Konrad Adenauer Foundation for European Policy Studies, to be paid out over ten years.

1990

-

Helmut Schmidt, the former chancellor of West Germany, speaks at the Council.

1992

-

The current US Secretary of Defense Dick Cheney speaks at the Council. He would go on to be the 46th vice president of the United States.

1995

-

Robert McNamara, the former defense secretary and master planner of the Vietnam War, speaks to the Council on mistakes of the war.

1996-2015 War on Terror

If, at the century's turn, the United States lacked an enemy and the Council lacked a focus, both were remedied, for better or worse, on 9/11, with the al Qaeda attacks on the World Trade Center and the Pentagon.

The United States declared war on terrorism and quickly became mired in the twin quagmires of Iraq and Afghanistan. The Council’s traditional focus on Europe shifted overnight to the Mideast, Islam, terrorism, and global inequities. In time, the Council’s focus migrated to China, to the rise of Third World countries, globalization, and, later, to populism, while Washington remained fixated on terrorism and the need for US dominance.

In Chicago, the Council probed a globalized world, with work on issues—trade, immigration, climate change, energy, global cities—that were perhaps visible first in the Midwest before they became national topics. The Council changed its name to the Chicago Council on Global Affairs in 2006 to reflect its shift toward exploring issues that transcend borders and traditional foreign policy. It also advanced its goal of becoming a think tank, first with a report on American foreign agriculture policy that became US government policy, then with original work on cities and the global economy. It established a Chicago-Shanghai dialogue and took a Chicago mayor to China.

Speakers During This Time

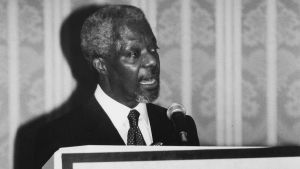

Secretary-General of the United Nations Kofi Annan speaks to the Council in 1997. Four years later, he would be co-recipient of the 2001 Nobel Peace Prize.

Journalist Fareed Zakaria speaks at the Council in 2003. He would return in 2016 to inaugurate the Council's new conference center.

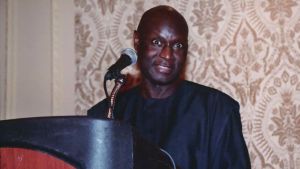

Former Under-Secretary-General of the United Nations Olara A. Otunnu speaks at the Council in 2006. He was later named President of the Uganda People's Congress.

Tony Blair, the former British prime minister, speaks to the Council in 2009.

Bill Gates, the founder of the Gates Foundation, gave the Council more than $11 million over the years, all for food and agricultural programs. He's pictured here speaking to the Council in 2011.

Secretary of State Hillary Clinton speaks at the 2012 Global Food Security Symposium: Advancing Food and Nutrition Security at the 2012 G8 Sumit.

Eventually, a Chicagoan became president and tried to extricate the nation from Iraq and Afghanistan. As these wars festered, an ambitious China and a resentful Russia became America’s great rivals. But the inequalities of globalization—or the government’s failure to deal with those inequalities—eroded the public trust in Washington, especially across the post-industrial Midwest, already described in reports by Council authors.

Play Video

Play Video

Continue exploring this era

1997

The Council celebrates its 75th anniversary.

1998

The Council faces challenges from other organizations, especially the Mid-America Committee (MAC). MAC was also a nonprofit world affairs council, based in Chicago, that was started in 1966 by former Council board member Thomas Miner.

The "Global Chicago" report, which urges reshaping of the Council's mission, is published.

1999

The Global Chicago Center is formed, funded by the MacArthur Foundation, and housed at the Chicago Kent College of Law. It becomes part of the Council in 2002.

2001

Marshall Bouton becomes Council president.

The militant Islamist terrorist group al-Qaeda attacks the United States in four coordinated efforts. Nearly 3,000 people are killed, both towers of the World Trade Center in New York City are destroyed, and part of the US Pentagon collapses.

2002

The Mid-American Committee (MAC) becomes part of the Council, initially serving as the Council's corporate program. Six MAC board members, including Lester Crown, join the Council board.

The Global Chicago Center becomes part of the Council. The center focused on studying Chicago's place in the global economy, and eventually expands to examine and compare great cities around the world.

2003

Chicago sponsors a two-day conference on world trade. The conference was timed to immediately follow a major meeting of trade ministers in Cancun, Mexico, on the progress of the Doha round of world trade talks.

The Council begins a series of task forces on immigration, Chicago's Mexican community, national energy policies, Chicago in the global economy, and the role of American Muslims after 9/11.

The Council launches its series of Heartland Papers: expert reports on the rural economy, Mexican immigration, biomass as a power source, and Midwestern higher education.

Council programs are dominated by debates on US policy in Iraq and Afghanistan.

2004

The Council publishes a new book, Global Chicago. The book is financed by the MacArthur Foundation and is the first attempt to study the urban impact of globalization by focusing on one transformed city.

Two years after joining the Council board, Lester Crown becomes chairman, a position he holds for ten years. He is the longest-serving chairman in Council history.

2006

The Council, until now the Chicago Council on Foreign Relations, changes its name to the Chicago Council on Global Affairs and updates its logo.

The Council organizes a trip to China with Chicago mayor Richard M. Daley.

A controversial Council appearance by University of Chicago Professor John Mearsheimer is canceled.

2008

The Council publishes the groundbreaking Global Cities Index with A.T. Kearney consulting firm.

A Council task force on agriculture in sub-Sahara Africa becomes an Obama Administration policy.

The Council establishes the Emerging Leaders Program, a selective fellowship for 20 to 22 participants each year, with the aim of arming a new generation of Chicago's business, civic, and social leaders with a deep understanding of global issues and a world view beyond Chicago.

2009

After receiving a three-year $3 million dollar grant from the Gates Foundation, the Council establishes its Global Agriculture Development Initiative (GADI), its first think tank center. GADI eventually becomes the Center on Global Food and Agriculture.

Council fellow Roger Thurow publishes his first Council-sponsored book "Enough".

To keep pressure on Congress after setting up its Global Agricultural Development Initiative, the Council opens its Washington, D.C. office.

2010

The Council creates a series of fellowships, including the Scholl Fellowship on China, the Gus Hart Fellowship on Latin America, and the Koldyke Global Teachers Program.

Major grants and funding come from the Gates Foundation, the McCormick Foundation, and others.

2011

The Council decides to revitalize its signature poll of Americans on US foreign policy by hiring its first full-time, in-house senior fellow. Now known as the Chicago Council Survey, the poll has been conducted annually since 2014.

2012

The day before the 2012 G8 Summit, the Council brought together senior global leaders to discuss new G8 efforts on food security and private sector investment in African agriculture.

Chicago hosts the NATO Summit, and the Council brings many related speakers to its stage, including US Ambassador to NATO Ivo H. Daalder.

The Council celebrates its 90th anniversary.

2013

Ivo Daalder, former US ambassador to NATO, becomes Council president.

2015

The Council publishes an important report offering recommendations to strengthen Ukraine's defense to deter further Russian aggression.

The Council launches the Chicago Forum on Global Cities, later renamed the Pritzker Forum on Global Cities.

On Global Cities, a book by Council distinguished fellow Richard C. Longworth, is published.

Lester Crown is honored at the 2015 Global Leadership Award Dinner for his extraordinary contributions to the city, the nation, and the world, and for his visionary leadership as chairman of the Council for more than 10 years.

Secretary Leon Panetta speaks on Leadership in War and Peace.

Explore full timeline

1997

-

The Council celebrates its 75th anniversary.

1998

-

The Council faces challenges from other organizations, especially the Mid-America Committee (MAC). MAC was also a nonprofit world affairs council, based in Chicago, that was started in 1966 by former Council board member Thomas Miner.

-

The "Global Chicago" report, which urges reshaping of the Council's mission, is published.

1999

-

The Global Chicago Center is formed, funded by the MacArthur Foundation, and housed at the Chicago Kent College of Law. It becomes part of the Council in 2002.

2001

-

August 13 -

Marshall Bouton becomes Council president.

-

September 11 -

The militant Islamist terrorist group al-Qaeda attacks the United States in four coordinated efforts. Nearly 3,000 people are killed, both towers of the World Trade Center in New York City are destroyed, and part of the US Pentagon collapses.

2002

-

The Mid-American Committee (MAC) becomes part of the Council, initially serving as the Council's corporate program. Six MAC board members, including Lester Crown, join the Council board.

-

The Global Chicago Center becomes part of the Council. The center focused on studying Chicago's place in the global economy, and eventually expands to examine and compare great cities around the world.

2003

-

September 15-16 -

Chicago sponsors a two-day conference on world trade. The conference was timed to immediately follow a major meeting of trade ministers in Cancun, Mexico, on the progress of the Doha round of world trade talks.

-

The Council begins a series of task forces on immigration, Chicago's Mexican community, national energy policies, Chicago in the global economy, and the role of American Muslims after 9/11.

-

The Council launches its series of Heartland Papers: expert reports on the rural economy, Mexican immigration, biomass as a power source, and Midwestern higher education.

-

Council programs are dominated by debates on US policy in Iraq and Afghanistan.

2004

-

October 10 -

The Council publishes a new book, Global Chicago. The book is financed by the MacArthur Foundation and is the first attempt to study the urban impact of globalization by focusing on one transformed city.

-

Two years after joining the Council board, Lester Crown becomes chairman, a position he holds for ten years. He is the longest-serving chairman in Council history.

2006

-

The Council, until now the Chicago Council on Foreign Relations, changes its name to the Chicago Council on Global Affairs and updates its logo.

-

The Council organizes a trip to China with Chicago mayor Richard M. Daley.

-

A controversial Council appearance by University of Chicago Professor John Mearsheimer is canceled.

2008

-

The Council publishes the groundbreaking Global Cities Index with A.T. Kearney consulting firm.

-

A Council task force on agriculture in sub-Sahara Africa becomes an Obama Administration policy.

-

The Council establishes the Emerging Leaders Program, a selective fellowship for 20 to 22 participants each year, with the aim of arming a new generation of Chicago's business, civic, and social leaders with a deep understanding of global issues and a world view beyond Chicago.

2009

-

After receiving a three-year $3 million dollar grant from the Gates Foundation, the Council establishes its Global Agriculture Development Initiative (GADI), its first think tank center. GADI eventually becomes the Center on Global Food and Agriculture.

-

June 23 -

Council fellow Roger Thurow publishes his first Council-sponsored book "Enough".

-

To keep pressure on Congress after setting up its Global Agricultural Development Initiative, the Council opens its Washington, D.C. office.

2010

-

The Council creates a series of fellowships, including the Scholl Fellowship on China, the Gus Hart Fellowship on Latin America, and the Koldyke Global Teachers Program.

-

Major grants and funding come from the Gates Foundation, the McCormick Foundation, and others.

2011

-

The Council decides to revitalize its signature poll of Americans on US foreign policy by hiring its first full-time, in-house senior fellow. Now known as the Chicago Council Survey, the poll has been conducted annually since 2014.

2012

-

May 18 -

The day before the 2012 G8 Summit, the Council brought together senior global leaders to discuss new G8 efforts on food security and private sector investment in African agriculture.

-

Chicago hosts the NATO Summit, and the Council brings many related speakers to its stage, including US Ambassador to NATO Ivo H. Daalder.

-

The Council celebrates its 90th anniversary.

2013

-

Ivo Daalder, former US ambassador to NATO, becomes Council president.

2015

-

February 2 -

The Council publishes an important report offering recommendations to strengthen Ukraine's defense to deter further Russian aggression.

-

The Council launches the Chicago Forum on Global Cities, later renamed the Pritzker Forum on Global Cities.

-

May 21 -

On Global Cities, a book by Council distinguished fellow Richard C. Longworth, is published.

-

June 10 -

Lester Crown is honored at the 2015 Global Leadership Award Dinner for his extraordinary contributions to the city, the nation, and the world, and for his visionary leadership as chairman of the Council for more than 10 years.

-

Secretary Leon Panetta speaks on Leadership in War and Peace.

2016-2022 From America First to Rebuilding Alliances

The Chicago Council was founded to combat isolationism and open America to the world. As its centenary neared, it found itself fighting the same old battles.

Across the world, populism bloomed. At home, Donald Trump, proclaiming an “America-First” nationalism, became president, largely on the votes of angry Midwesterners in the Council’s own back yard. In this debate, the Council, while nonpartisan, was not neutral.

Council programming strove to explain these new forces, at home and abroad. At the same time, its think-tank activities multiplied, to take on issues—such as trade, immigration, and especially global cities—where the Council, by virtue of its heartland location, had a comparative advantage. The Pritzker Forum on Global Cities debated the place of major cities in an urban-vs-rural world.

Speakers during this time

Play Video

Play Video

Academy Award winner Sharmeen Obaid-Chinoy speaks at the Council's 2016 Global Leadership Awards Dinner about fighting injustice through her documentary films.

Play Video

Play Video

Lael Brainard, Federal Reserve Board of Governors member, joins the Council in 2016 to discuss the economic outlook for the United States and monetary policy implications.

Play Video

Play Video

The mayor of London Sadiq Khan speaking at the Council in 2016.

Play Video

Play Video

John Kerry, the Secretary of State, speaking at the Council in 2016.

Nana Akufo-Addo, the President of Ghana, visits the Council in 2019 for a special roundtable discussion.

Play Video

Play Video

General James Mattis, former US Secretary of Defense, speaks at the 2019 Lester Crown Lecture.

Play Video

Play Video

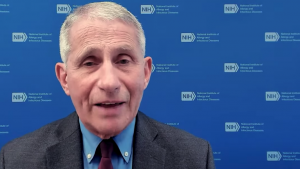

Dr. Anthony Fauci, director of the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases (NIAID) and Chief Medical Advisor to President Biden, speaks at a virtual Pritzker Forum program in 2021.

Play Video

Play Video

US Secretary of the Treasury Janet L. Yellen speaks to a Council audience at a virtual program in 2021.

New challenges mounted. Trump’s supporters jeered at the very way the Council viewed the world. Racial protests forced the Council to study its own obligations to diversity. The COVID-19 pandemic closed its offices. Everything—programs and studies alike—became remote. Fortunately, brand-new technology enabled the Council to spread its word more widely than ever, creating a national and international audience.

Related Video

Play Video

Play Video

On November 1, 2017, Vice President Biden examines America's leadership in a world of uncertainty.

Play Video

Play Video

On December 16, 2021, Madeleine Albright and Condoleezza Rice discuss their experiences as trailblazers in foreign policy.

As it approached its centenary, the Council was the biggest world affairs council west of the Beltway. If it sought new audiences, it remained mostly an elite organization. As it did 100 years ago, it insisted that America’s proper view is outward and its proper policy in the world is openness.

Continue exploring this era

2016

The University of Pennsylvania's survey of think tanks names the Council the number one "think tank to watch." The Council also placed on the list of the "Best Managed Think Tanks in the US" and "Top Defense and National Security Think Tanks in the US."

The Council moves into its current offices in the Prudential-Two building and opens its own Conference Center. The new space enables live streaming of events to thousands of online viewers.

The first episode of the Council's foreign policy podcast Deep Dish airs. In the episode, experts discuss the politicization of monetary policy.

Donald Trump is elected president. Council president Ivo Daalder writes in an open letter, "We are nonpartisan but not neutral. We believe in ideas and we believe in engagement. We have fought isolationism before, and we will do it again."

2018

The Council receives $4 million from the McCormick Foundation and renames the main hall in its new conference center the Robert R. McCormick Foundation Hall.

The Council receives $10 million from the family of Lester Crown. The gift establishes the Lester Crown Center on US Foreign Policy, which focuses on research on foreign policy issues, among other things.

Leah Zell and Samuel Scott become co-chairs of the Council board, the first woman and African-American to hold the post.

2019

The Council receives a $5 million multi-year commitment from the Pritzker Foundation to support its annual three-day global cities forum. The forum is renamed the Pritzker Forum on Global Cities.

2020

The global COVID-19 pandemic begins.

All Council activities and programs go remote. Ivo Daadler begins the World Review event series.

2021

Joe Biden is inaugurated as US president.

The US withdrawal from Afghanistan is complete. The Council explores the lessons from past military evacuations in Vietnam and South Sudan and examines what they tell us about the coming days in Afghanistan.

Explore full timeline

2016

-

The University of Pennsylvania's survey of think tanks names the Council the number one "think tank to watch." The Council also placed on the list of the "Best Managed Think Tanks in the US" and "Top Defense and National Security Think Tanks in the US."

-

The Council moves into its current offices in the Prudential-Two building and opens its own Conference Center. The new space enables live streaming of events to thousands of online viewers.

-

September 16 -

The first episode of the Council's foreign policy podcast Deep Dish airs. In the episode, experts discuss the politicization of monetary policy.

-

Donald Trump is elected president. Council president Ivo Daalder writes in an open letter, "We are nonpartisan but not neutral. We believe in ideas and we believe in engagement. We have fought isolationism before, and we will do it again."

2018

-

The Council receives $4 million from the McCormick Foundation and renames the main hall in its new conference center the Robert R. McCormick Foundation Hall.

-

The Council receives $10 million from the family of Lester Crown. The gift establishes the Lester Crown Center on US Foreign Policy, which focuses on research on foreign policy issues, among other things.

-

June 20 -

Leah Zell and Samuel Scott become co-chairs of the Council board, the first woman and African-American to hold the post.

2019

-

January 16 -

The Council receives a $5 million multi-year commitment from the Pritzker Foundation to support its annual three-day global cities forum. The forum is renamed the Pritzker Forum on Global Cities.

2020

-

The global COVID-19 pandemic begins.

-

All Council activities and programs go remote. Ivo Daadler begins the World Review event series.

2021

-

January 20 -

Joe Biden is inaugurated as US president.

-

August 30 -Listen to the Audio

The US withdrawal from Afghanistan is complete. The Council explores the lessons from past military evacuations in Vietnam and South Sudan and examines what they tell us about the coming days in Afghanistan.

The Council's Second Century

With political, cultural, and technological changes and disruptions driving historical shifts in the global order, the Council’s mission is as critical today as when it was founded in 1922. We’ve spent the past 18 months planning and preparing for the Council’s second century and how we can empower more people to help shape our global future.

While "Chicago and the World" reflects on the Council’s past, in 2022, we will turn our attention to the opportunities and challenges that lie ahead for the Council, for Chicago, for our nation, and for the world. We’re excited about our future and about you being part of it. Members and donors have always made what we do possible. Thank you.

Related Videos

Play Video

Play Video

Author of "Chicago and the World" Richard Longworth joins Carol Marin to reflect on the Council’s century of global influence.

Play Video

Play Video

Richard Longworth talks with Council President Ivo H. Daalder and former Council presidents John E. Rielly and Marshall M. Bouton

On March 10, 2022, the Council celebrated its centennial anniversary at a gala dinner honoring President Barack Obama and cellist Yo-Yo Ma for their extraordinary contributions toward creating a more open and promising world for all.

Play Video

Play Video

Generous matching grants from Bruce and Martha Clinton and Bob and Susan Arthur made this book possible, along with support from Pat and Ron Miller and Adele Simmons.