Biden-era surveys affirm continued support for the intelligence community but also signal growing partisanship.

Results of The University of Texas at Austin’s 2021 and 2022 nationwide surveys of public attitudes on US Intelligence confirm that most Americans believe US intelligence agencies are vital to protecting the nation and effective in achieving their assigned tasks. However, they also find that partisan preference plays a significant—and growing—role in shaping public views of the Intelligence Community’s performance and proper oversight authority. Moreover, public concerns about potential violations of citizens’ privacy rights and civil liberties persist despite efforts by the Intelligence Community to improve transparency and public understanding.

Key Takeaways

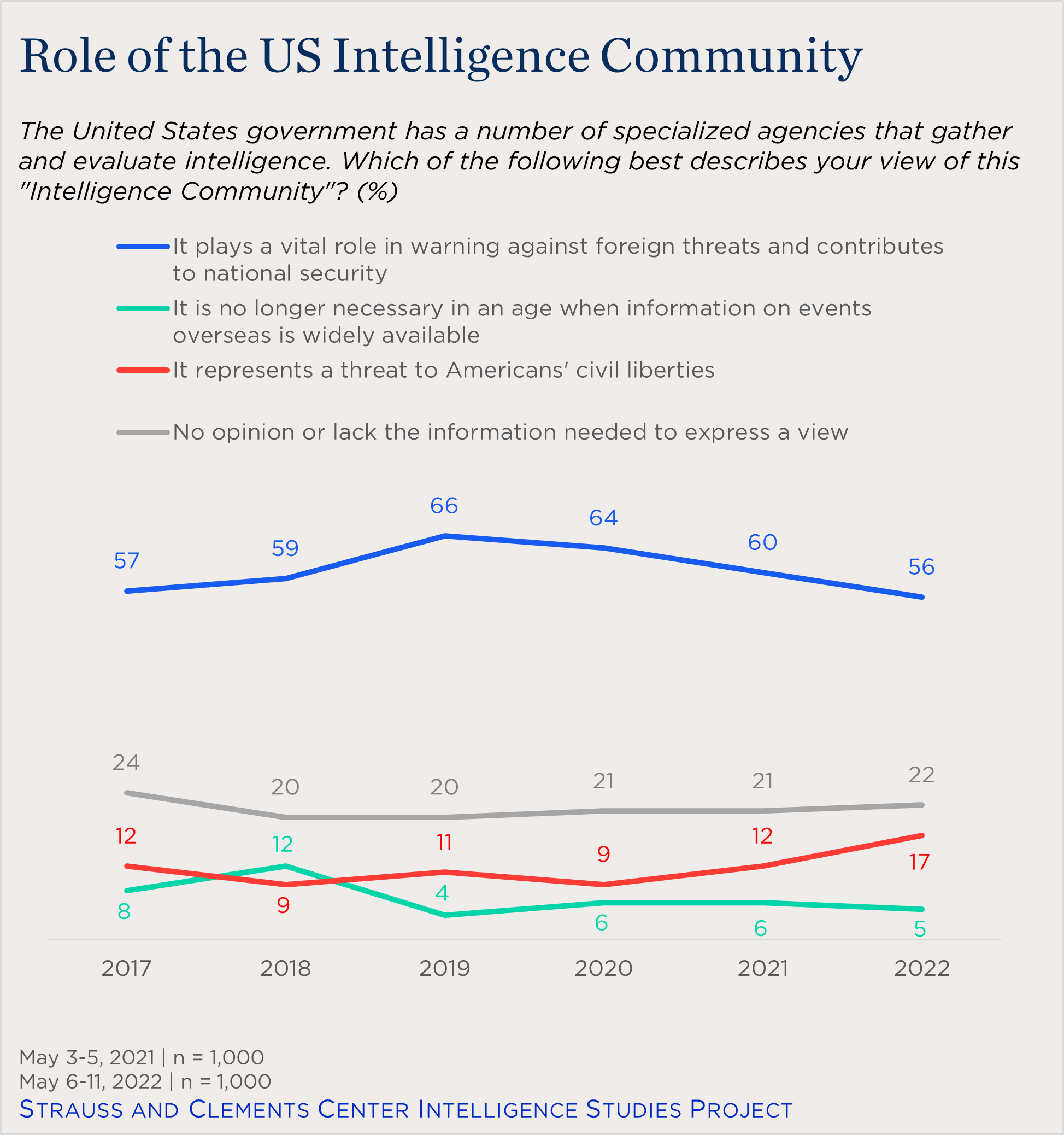

- Most Americans expressed the view that the Intelligence Community (IC) plays a vital role in protecting the nation—60 percent in 2021, and 56 percent in 2022.

- Few respondents believed the IC was “no longer necessary” but a sizeable, and growing, number of Americans thought the IC represented a threat to their civil liberties.

- An overwhelming majority of Americans regarded the IC agencies as highly capable in accomplishing specialized missions like preventing terror attacks and learning the plans of our adversaries. However, fewer than half of respondents believed that the intelligence agencies respected their privacy and civil liberties.

- There were notable partisan differences in views of US Intelligence. Between the 2020 and 2021 surveys—including the transition between the Trump and Biden administrations—Democrats who believed that the IC was vital increased while Republican support for the IC decreased significantly.

- Americans also appear increasingly inclined to judge the performance of the intelligence agencies based on their partisan alignment with the incumbent president.

- Respondents who “disapproved” of President Joe Biden were much less inclined to regard the IC as vital and more likely to label the IC as a threat to civil liberties.

Transparency, Public Trust, and Democratic Legitimacy

The unlawful disclosure of sensitive electronic surveillance programs by former National Security Agency (NSA) contractor Edward Snowden early last decade seriously challenged the US IC’s public standing. Neither then-President Barack Obama nor key congressional leaders who were informed of these programs acted forcefully to reassure Americans that the NSA’s actions were effective, lawful, and implemented in a manner that respected their civil liberties. Director of National Intelligence (DNI) James Clapper (2010-2017) responded to this crisis in public confidence by launching a “Transparency Initiative” designed to improve the public’s understanding of the IC’s mission, the laws, policies and practices that constrain the IC, as well as how such secret activities were supervised and overseen. 1 In 2017, UT-Austin launched a long-term polling project to shed light on Americans’ actual perceptions of the intelligence agencies and to test the claim that efforts by IC agencies to be more open would enhance their support and democratic legitimacy. 2

President Donald Trump’s first DNI Dan Coats (2017-2019) endorsed the IC’s commitment to transparency in an internal directive 3 and acknowledged in his 2019 National Intelligence Strategy that more openness would be “necessary to earn and maintain public trust.” 4 In practice, though, Trump administration intelligence officials deliberately lowered their public profiles to avoid triggering an irascible and vindictive boss. For example, IC leaders avoided open testimony at the worldwide threat hearings—the single opportunity in most years for the American people to hear directly from senior intelligence officials. 5 The few public acts by Trump’s last DNI, John Ratcliffe (2020-2021), included the selective declassification of documents related to Russia’s interference in the 2016 US election apparently intended to bolster the incumbent’s reelection prospects, notwithstanding the risks to intelligence sources and the IC’s nonpartisan ethos. 6

Since taking office, current President Joe Biden has acted to restore public confidence in essential government institutions like the intelligence agencies. In testimony delivered at her confirmation hearing, incoming DNI Avril Haines (2021- ) promised to “prioritize transparency” in order to enhance the public’s confidence in the competence, integrity, and nonpartisanship of US intelligence. 7 DNI Haines resumed the custom of presenting an IC Annual Threat Assessment in open session and cited that exercise as evidence of the Office of the Director of National Intelligence’s (ODNI) commitment to public transparency. 8 According to media reports, the ODNI is also playing a central role in a National Security Council (NSC)-led process to revise the Obama-era executive order that governs classification of national defense information. 9

American intelligence leaders are not alone in recognizing a link between excessive secrecy and popular support. Even the head of the notoriously tight-lipped British Secret Intelligence Service has called for a “sea change” in that service’s “culture, ethos and way of working” in favor of greater openness. 10

Despite President Trump’s public criticism of IC leaders, our polling confirmed a durable reservoir of public confidence in the intelligence agencies. At the same time, our surveys have revealed persistent differences in public attitudes on US intelligence based on age, gender, and party affiliation as well as specific topics that reliably trigger concern.

These insights are intended to assist current IC leaders who have expressed interest in reinvigorating efforts to increase transparency and design public-facing programs that educate and inform a broader public about the work of our intelligence agencies. 11 For example, our data have indicated that support for the IC is weakest among younger Americans. Skepticism about the IC’s commitment to protecting privacy rights and civil liberties is widespread. While the IC’s overall support is bipartisan, sharp party differences emerged when survey respondents were asked about the IC’s role in presidential policymaking, appropriate roles of the president and Congress in overseeing the intelligence agencies, and the protections that US intelligence should provide to the personal information of foreigners. Closing these partisan gaps by reinforcing the apolitical ethos of American intelligence should be a priority for intelligence leaders and the current administration.

Views of the US Intelligence Community

Data from our 2021 and 2022 surveys affirmed the IC’s continued support by a strong majority of Americans (see Figure 1). Each year since this project’s inception roughly six in 10 respondents have agreed with the statement that the IC “plays a vital role in warning against foreign threats and contributes to our national security.” Only a small number of respondents—5 percent in 2022, unchanged from 6 percent in 2021—agreed with the claim that the IC “is no longer necessary.”

The proportion of respondents who believed the IC represents a threat to civil liberties was 17 percent in 2022, up from 12 percent in 2021 and slightly elevated from a customary range of 9 percent to 12 percent. Roughly one in five Americans claimed to have no opinion or lacked the information needed to shape a view on US Intelligence.

More interesting insights emerged from the stratified data. For example, support for the IC correlates directly to age. Two-thirds (67%) of Silent Generation respondents and 65 percent of Baby Boomers viewed the IC as vital while only 42 percent of Gen Z participants expressed that view. Slightly more men than women expressed support for the IC in 2022, but women were twice as likely as men in the most recent poll (30% and 14%, respectively) to admit that they had no opinion or lacked the information needed to express a view on the IC’s utility. Similarly, in 2022, Black respondents (31%) were significantly more likely than White respondents (20%) to claim they lacked information or had no view on the IC.

The most notable shift detected in the recent survey data on public attitudes on the IC was an increase in partisan differences. The number of Democrats who agreed that the IC was vital jumped from 66 percent in 2020 to 73 percent in 2021 to 70 percent in 2022. Among Republicans, support for the IC fell from 71 percent in 2020 to 58 percent and 51 percent in 2021 and 2022, respectively. Only 6 percent of Democrats expressed the view that the IC represented a threat to civil liberties in 2022 while 23 percent of Republicans agreed with that claim, up from only 6 percent two years earlier during a Republican administration.

The influence of partisanship on general views of US Intelligence was confirmed by a survey question regarding a respondent’s approval of President Joe Biden. Compared to those who strongly or somewhat approved, participants who strongly or somewhat disapproved of Biden were significantly less inclined to view the IC as vital to national security (46% compared to 72%) and much more likely to regard the intelligence agencies as a threat to civil liberties (27% compared to 6%).

Respondents categorized as “low knowledge” and “high knowledge” (based on questions about the identity of several European political leaders) were both likely to express support for the IC (53% and 62%, respectively) in 2022, but the more knowledgeable participants were almost twice as likely as their less knowledgeable counterparts to identify the IC as a threat to Americans’ civil liberties (25% and 13%).

Effectiveness of the US Intelligence Community

To understand more precisely why Americans hold a generally favorable view of US Intelligence, we asked respondents how effective the IC is in accomplishing a number of its key missions: counterterrorism, collecting foreign intelligence, influencing conditions abroad (covert action), supporting national security policymaking, and counterintelligence.

Continuing a pattern established in previous surveys, in 2021 and 2022, about eight in 10 Americans rated our intelligence agencies as effective or highly effective in preventing terror attacks as well as learning the plans of hostile governments (see Figure 2). In these two surveys, smaller but still solid majorities viewed the IC as effective in “influencing events overseas in favor of the US” (62% in 2022, similar to 2021’s 66%) as well as “protecting sensitive defense information from foreign governments” (69% in both years).

As in previous years, fewer than half of the respondents judged the IC as effective or highly effective in “respecting the privacy and civil liberties of Americans.” The percentage of respondents holding this view dropped from 49 percent in 2021 to 44 percent in 2022 with the greatest skepticism expressed by men, Republicans, Independents, and “high knowledge” respondents. In 2022, 59 percent of respondents who identified as Democrats credited the IC with respecting civil liberties while only 34 percent of Republicans held that view.

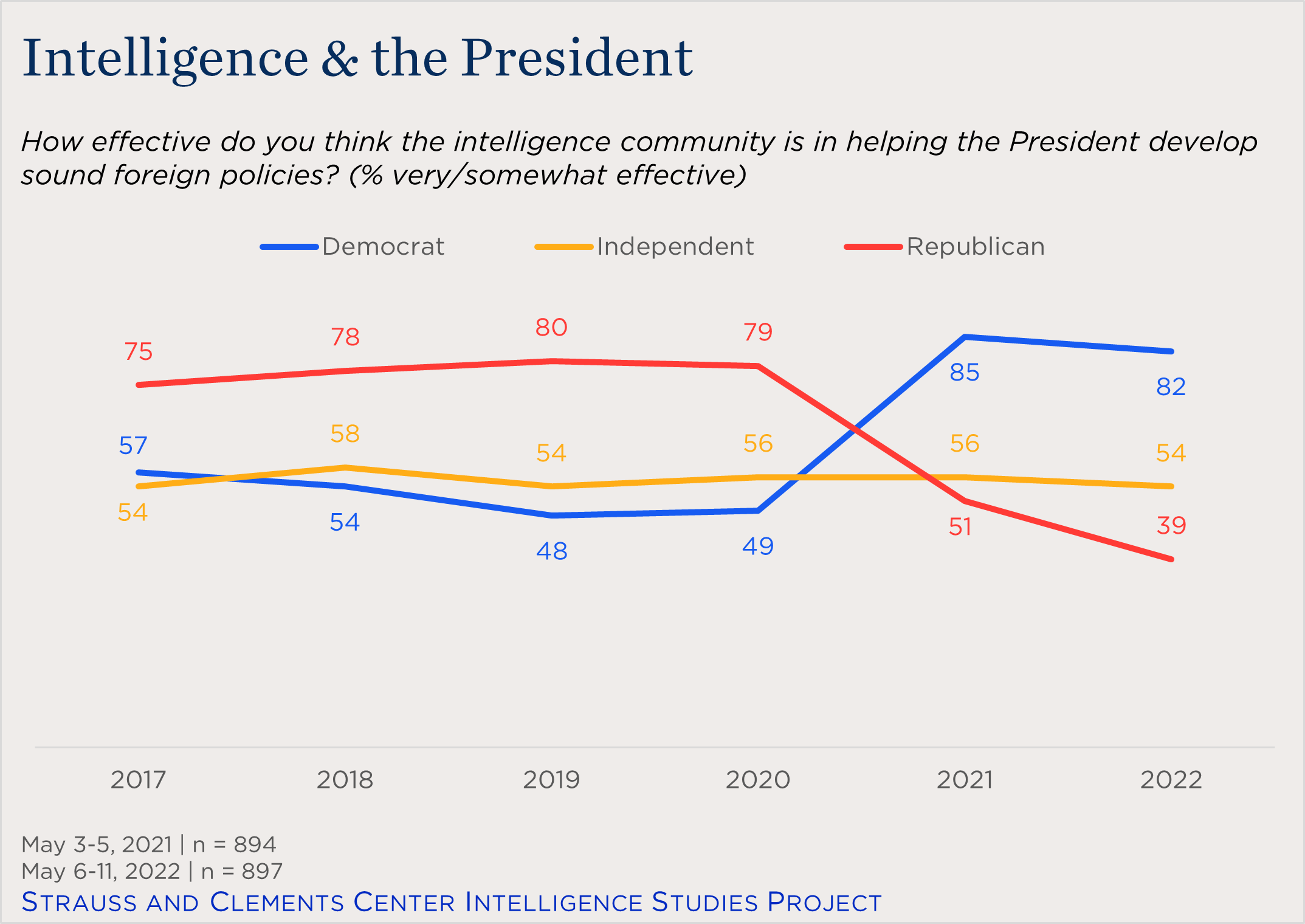

Growing partisan disparities in Americans’ views on the IC were reflected in responses regarding the IC’s effectiveness in “help[ing] the President develop sound foreign policies” (see Figure 3). In our 2019 and 2020 reports, we noted that eight in 10 Republicans thought the IC was effective in helping then-President Trump develop sound foreign policies while fewer than half of those who identified as Democrats held that view. We noted then that these results were more likely based on disparate perceptions of the incumbent president rather than actual knowledge of the IC’s (largely nonpublic) performance in supporting the policymaking process.

Foreseeably, these survey results reversed when a president of a different party (Biden) moved into the White House and assumed principal responsibility for developing foreign policies. The 2021 poll reflected that 85 percent of Democrats believed the IC provided effective support to the president while only 51 percent of Republicans expressed that view.

The tendency of Americans to judge the performance of our intelligence agencies by their partisan alignment with the incumbent president is potentially dangerous for institutions whose impact is based on credibility and whose credibility is linked to the ability to produce objective, nonpartisan assessments. IC leaders should design transparency programs and seek public opportunities to reinforce the strong apolitical ethos that distinguishes US intelligence agencies from their counterparts in authoritarian and less democratic systems.

Responsibilities of the US Intelligence Community

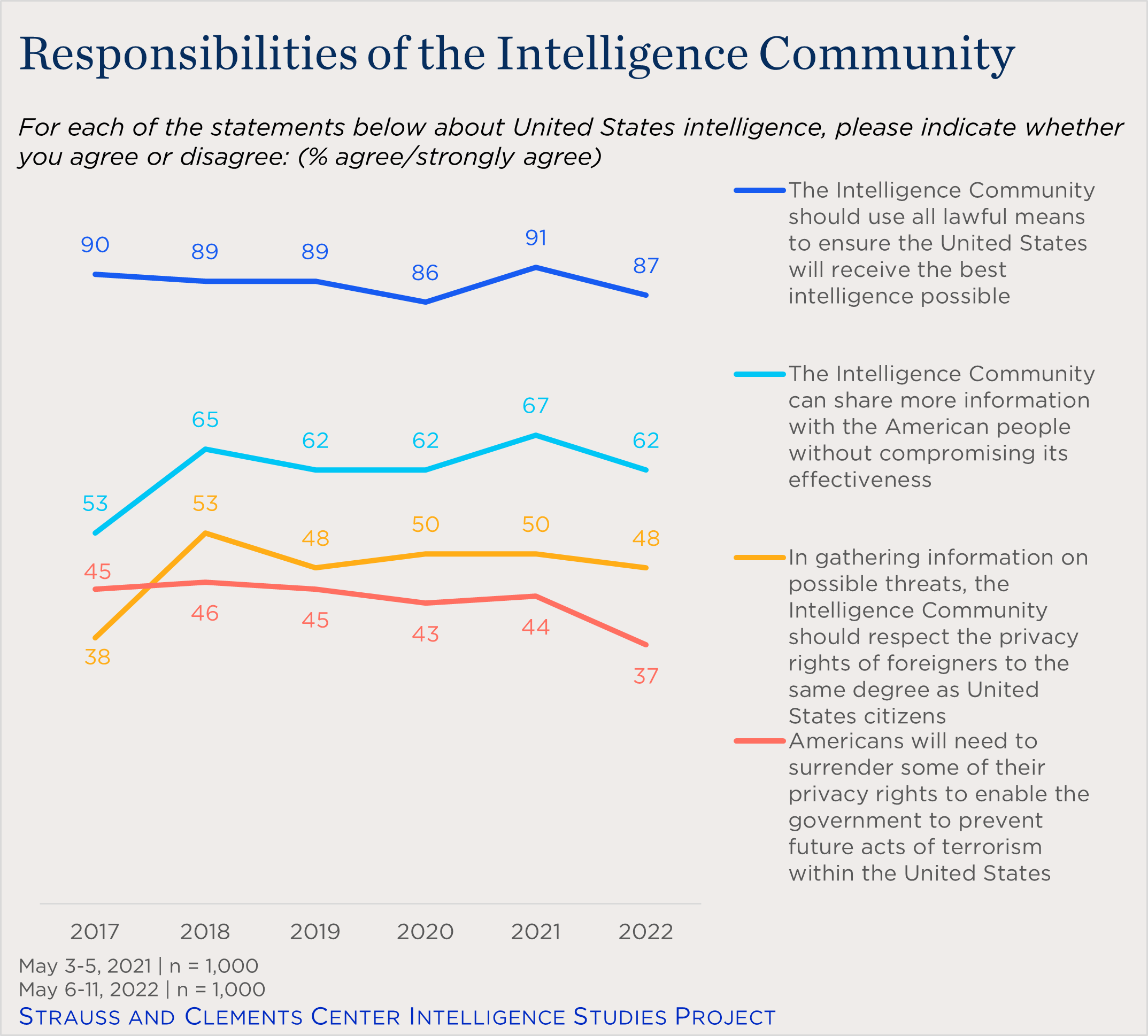

Each year we ask survey participants to evaluate statements regarding, inter alia, the IC’s responsibilities: 1) to use all lawful means to accomplish their missions; 2) to protect the personal information of foreigners; and 3) to share information with the US public. The topline values for these responsibilities in Figure 4 have been remarkably stable over the life of the project. But this consistency masks potentially significant differences in how certain groups view the IC’s responsibilities.

Beginning with President Ronald Reagan in 1981, US presidents of both parties have charged the IC to use “all reasonable and lawful means” to provide the government with the best possible intelligence. 12 In 2021 and 2022, nearly nine in 10 respondents once again agreed or strongly agreed with this aspirational statement. Without formally amending Reagan’s order, in 2014 then-President Obama directed that IC agencies engaged in electronic surveillance must provide “safeguards for the personal information of all individuals regardless of nationality.” 13 The voluntary extension of privacy rights to foreign nationals became a key part of the Obama and Trump administrations’ response to complaints by European allies about unconstrained data collection by US intelligence agencies.

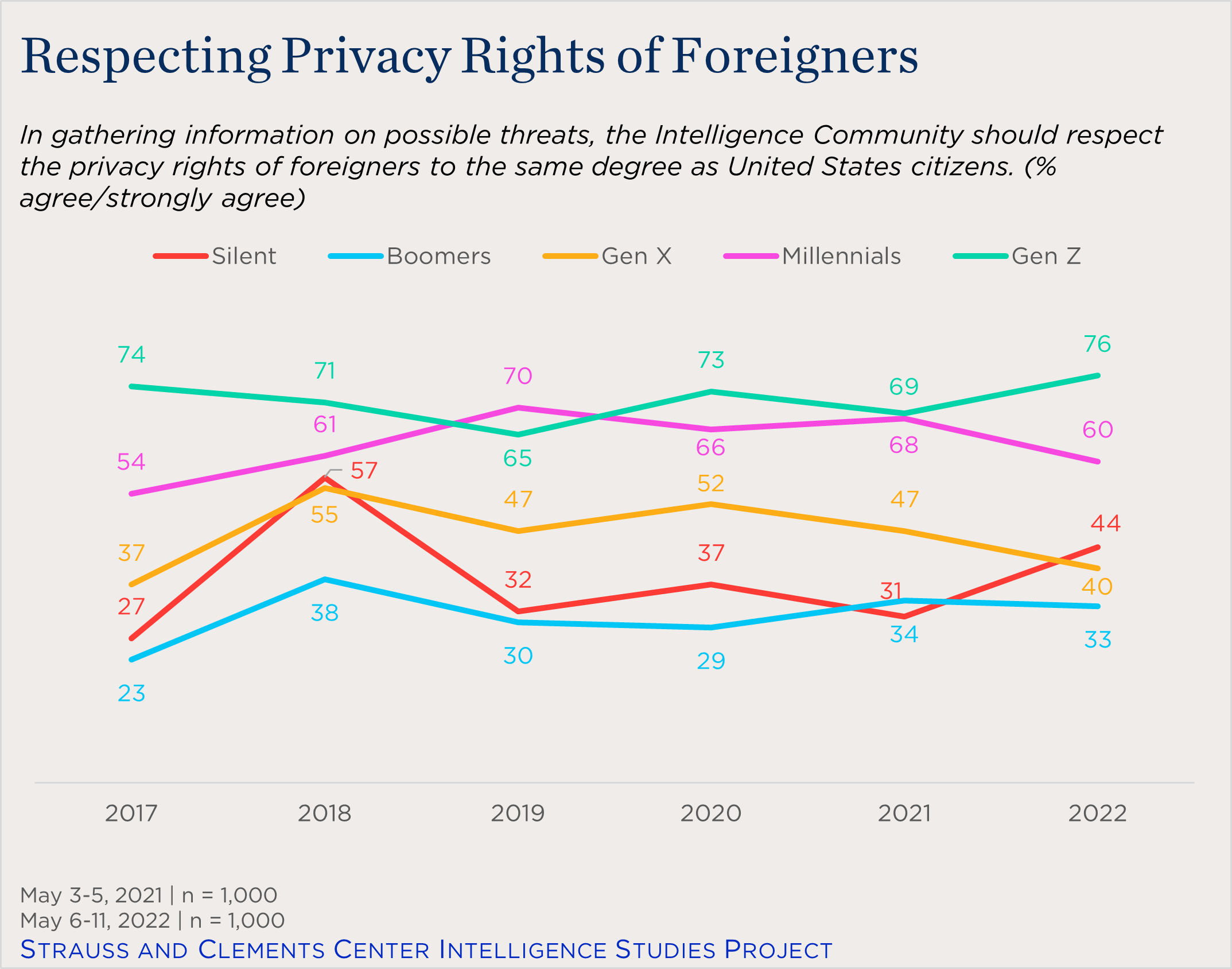

Our two most recent surveys reflect a fairly even split (48% in 2022, similar to 50% in 2021) in support for the requirement that US intelligence agencies respect the privacy rights of foreigners to the same extent as those of US citizens. But wide disparities in attitude exist based on age and party affiliation. For example, in 2022, 76 percent of Gen Z respondents supported the extension of privacy protections to foreigners while only 33 percent of Baby Boomers agreed with this voluntary restriction on intelligence collection (see Figure 5).

Partisan differences on this question are similarly stark. In 2022, 61 percent of Democrats expressed support for constraining intelligence collection involving foreigners while only 28 percent of Republicans supported such limits.

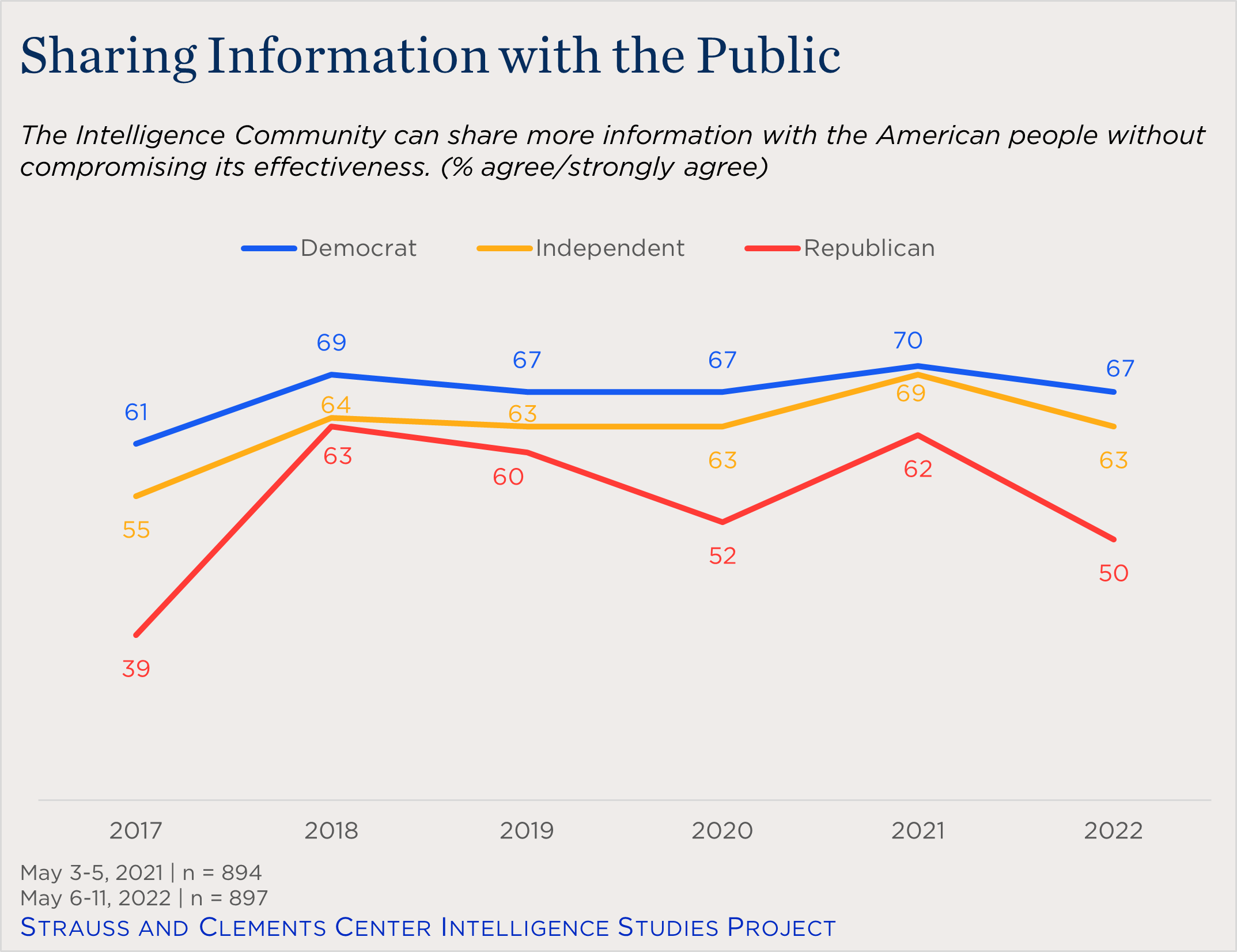

Regarding secrecy, a majority of Americans (62%, similar to 2021’s 67%) believed the IC could share more information with the public without compromising its effectiveness. Younger and Democratic respondents were somewhat more inclined to support greater transparency. In the most recent survey, 67 percent of Democrats supported greater information sharing with the public compared with 50 percent of respondents who identified as Republicans (see Figure 6).

Our 2017 baseline poll and each successive annual survey has revealed considerable public uncertainty over which government officials and institutions are responsible for overseeing the intelligence agencies. The 2021 and 2022 surveys yielded similar inconclusive results (see Figure 7).

Respondents were asked to select the institution primarily responsible for monitoring the activities of the US intelligence agencies from a short list. In 2022, the NSC was selected by 23 percent of respondents, the director of the respective agency by 22 percent, and Congress by 18 percent. Seventeen percent of respondents selected the federal courts and judges while 11 percent of participants assigned this responsibility directly to the president. Fewer than eight percent believed that news media and investigative journalists were principally responsible for overseeing our intelligence agencies.

In our 2020 report, we flagged partisan disparities concerning the oversight role played by the president and Congress. We observed that Republicans were twice as likely as Democrats to identify the president as the official responsible for ensuring that our intelligence agencies “act within the law and in the country’s best interest.” We attributed that disparity to Republicans’ trust and confidence in then-President Trump. During that same polling cycle (while both houses of Congress were in Democratic hands), 27 percent of participating Democrats believed Congress had a primary intelligence oversight role while only 11 percent of Republicans expressed that view.

When the White House changed hands in 2021, the percentage of Democrats that assigned intelligence oversight to the president increased from nine percent to 17 percent 14 while the percentage of Republicans who charged the president with intelligence oversight dropped from 23 percent to 13 percent. Our surveys indicate that partisan affiliation influences not only how Americans rate the IC’s effectiveness, respect for civil liberties, and treatment of foreigners but also which institutions should bear principal responsibility for supervising and overseeing its work.

Conclusion

The US intelligence agencies, like all other government institutions, ultimately depend on the public’s support for resources, policy impact and institutional resiliency. Earning and maintaining the public’s trust poses a unique challenge for organizations that must operate largely in secret to accomplish their missions. Our polling confirms that most Americans believe their intelligence agencies are vital to protecting the nation and effective in achieving their assigned tasks. These attitudes did not change materially with the transition from a presidential administration that was openly hostile to the IC to one that is publicly supportive of the intelligence agencies. There is also no reflection in the survey results that programs and activities aimed at increasing transparency and improving the public’s understanding of American Intelligence are having an impact. For officials designing programs aimed at explaining or correcting misperceptions about the IC, our polling highlights a persistent concern that the IC does not respect citizens' privacy and civil liberties rights and growing partisan differences about the IC’s effectiveness and appropriate supervision and oversight.

- 1Principles of Intelligence Transparency for the Intelligence Community, 2015. https://www.dni.gov/index.php/ic-legal-reference-book/the-principles-of-intelligence-transparency-for-the-ic

- 2Data and analysis from surveys in 2017, 2018, 2019, and 2020. (2017) https://globalaffairs.org/research/public-opinion-survey/glasnost-us-intelligence-will-transparency-lead-increased-public; (2018) https://globalaffairs.org/research/public-opinion-survey/2018-public-attitudes-us-intelligence; (2019) https://globalaffairs.org/research/public-opinion-survey/2019-public-attitudes-us-intelligence; (2020) https://globalaffairs.org/research/public-opinion-survey/public-attitudes-us-intelligence-2020

- 3ODNI, Intelligence Community Directive 107, February 28, 2018. https://www.dni.gov/files/documents/ICD/ICD-107.pdf

- 4ODNI, National Intelligence Strategy, 2019. https://www.dni.gov/index.php/newsroom/reports-publications/item/1943-2019-national-intelligence-strategy

- 5Martin Matishak, “Intel Agencies Push to Close Threats Hearing after Trump Outburst,” Politico, January 15, 2020. https://www.politico.com/news/2020/01/15/intel-agencies-threats-hearing-trump-099494

- 6ODNI, DNI Ratcliffe Statement on Declassification of Transcripts, May 29, 2020. https://www.dni.gov/index.php/newsroom/press-releases/item/2124-dni-ratcliffe-statement-on-declassification-of-transcripts

- 7SSCI Open Hearing: On the Nomination of Avril D. Haines to be Director of National Intelligence, January 19, 2021. https://www.intelligence.senate.gov/sites/default/files/hearings/t-ahaines-011921.pdf

- 8Annual Threat Assessment of the U.S. Intelligence Community, February 2022. https://www.dni.gov/index.php/newsroom/reports-publications/reports-publications-2022/item/2279-2022-annual-threat-assessment-of-the-u-s-intelligence-community

- 9Bryan Bender, “White House Launches New War on Secrecy,” Politico, August 23, 2022. https://www.politico.com/news/2022/08/23/white-house-war-on-secrecy-00053226

- 10Open Book, “Britain’s Chief Spook Sees China as the Main Intelligence Threat,” Economist, December 4, 2021. https://www.economist.com/britain/2021/12/04/britains-chief-spook-sees-china-as-the-main-intelligence-threat

- 11Greg Myre, “Avril Haines Takes Over as Intelligence Chief at a ‘Challenging Time,’” National Public Radio, February 28, 2021. https://www.npr.org/2021/02/28/971985826/avril-haines-takes-over-as-intelligence-chief-at-a-challenging-time

- 12EO 12333 (1981). https://www.archives.gov/federal-register/codification/executive-order/12333.html

- 13Presidential Policy Directive-28 (2014). https://obamawhitehouse.archives.gov/the-press-office/2014/01/17/presidential-policy-directive-signals-intelligence-activities

- 14We note that this apparent post-election spike in support among Democrats for presidential oversight of intelligence may have been temporary. In 2022, the level of support by Democrats again measured only 11%.

The data cited in this report derives from two national surveys conducted by YouGov from May 3 to May 5, 2021 and May 6 to 11, 2022. In 2021, YouGov interviewed 1210 respondents who were matched down to a sample of 1,000 to produce a final dataset. Similarly, in 2022, 1,019 respondents were interviewed and matched to the final sample of 1,000. The sampling margin of error is +/- 3.3 percentage points.

The respondents were matched to a sampling frame on gender, age, race, and education. The frame was constructed by stratified sampling from the full American Community Survey (ACS) 1-year sample with selection within strata by weighted sampling with replacements (using the person weights on the public use file), with the 2022 survey using the 2019 ACS, and the 2021 survey using the 2018 ACS. The matched cases were weighted to the sampling using propensity scores. The matched cases and the frame were combined and a logistic regression was estimated for inclusion in the frame. The propensity score function included age, gender, race/ethnicity, years of education, and region. The propensity scores were grouped into deciles of the estimated propensity score in the frame and post-stratified according to these deciles.

The weights were then post-stratified on 2016 and 2020 presidential vote choice, and a four-way stratification of gender, age (4-categories), race (4-categories), and education (4-categories), to produce the final weight.

Related Content

Public Opinion

Public Opinion

A final Trump-Era survey confirms broad popular support for the intelligence community and reveals opportunities for greater transparency.

Defense and Security

Defense and Security

A 2019 survey confirmed broad support of US intelligence agencies, despite limited transparency and persistent criticism from President Donald Trump.

Public Opinion

Public Opinion

Despite this unprecedented antagonism from President Trump’s administration, most Americans, including Republicans, continued to express confidence in the intelligence community.

Public Opinion

Public Opinion

A University of Texas polling project from the Chicago Council on Global Affairs found Americans consider the work of the intelligence community effective.