With 20-Year Hindsight, Public Opinion and the Iraq War

To be suspicious of Iraq was part of the American zeitgeist long before 2003, survey data show.

This week marked the 20th anniversary of the Iraq war. Readers have likely seen numerous articles reflecting on the legacy of that military conflict. Some commentators have processed the lessons learned from that intervention; some have outlined the lessons not learned; and a few articles even discussed the war’s impact on US public opinion.

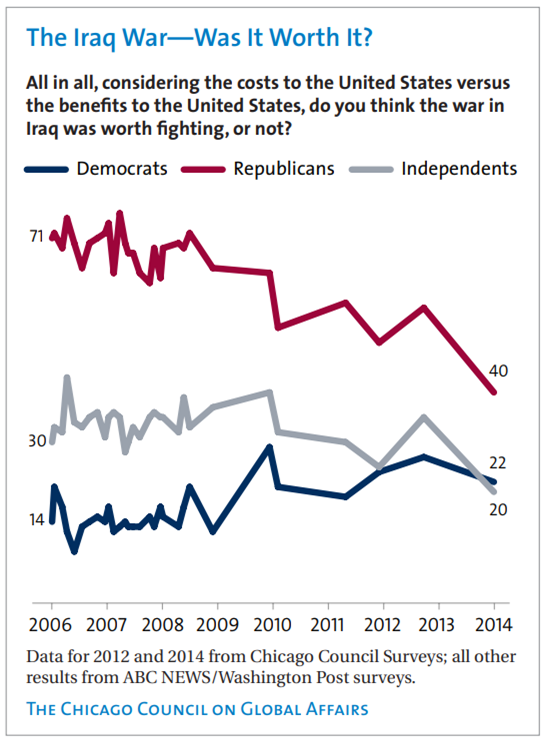

With hindsight and a contemporary lens, many—albeit not all—authors have described the war in terms like a “fiasco in the mold of Vietnam,” “a grievous error … based on scanty and deeply flawed intelligence,” or “a mistake from its inception.” And it’s not just the experts who feel this way. By late 2004, a majority of Americans started to say that the Iraq war was not worth the costs in Washington Post/ABC News polling. The last time the Chicago Council on Global Affairs asked the public to assess the war in 2014, only 40 percent of Republicans and 22 percent of Democrats thought it had been worth fighting.

In a different sort of take, Hal Brands characterized the war as an “understandable tragedy, born of honorable motives and genuine concerns.” He points out that even prior to the September 11 attacks, many Americans supported a more muscular Iraq policy.

Before George W. Bush announced US plans to intervene in Iraq, Bill Clinton had been dealing with his own showdowns with Saddam. In 1993, Clinton ordered cruise missile strikes against the Iraqi Intelligence Service headquarters in Baghdad after US intelligence reports that Saddam had tried to assassinate former President George H.W. Bush. Also during Clinton’s presidency, Congress passed the 1998 Iraq Liberation Act, with large majorities in both congressional houses, setting US policy on a path to “seek to remove the Saddam Hussein regime from power in Iraq and to replace it with a democratic government.” And in December 1998, Clinton ordered air strikes against Iraq because it refused to cooperate with UN weapons inspectors.

To be suspicious of Iraq was part of the zeitgeist of the times. Public opinion was also quite alarmed by Saddam’s intent. In February 1998, Gallup polls found that 88 percent of Americans thought Iraq represented a threat to world peace and seven in 10 said they would support a US attack on Iraq (all polls cited in this post are from Roper’s Ipoll database unless otherwise linked). In December 1998, after the air strikes, nearly eight in 10 Americans approved of the decision in ABC/Washington Post and Gallup polls. And by February 1999, 74 percent of Americans told Gallup interviewers that they would support using military force to remove Saddam from power.

Fast forward to 2003. The US invasion began on March 20 of that year, and several polls found majority support in favor of the military action. For example, in both a late March Pew survey and an April CNN poll, 71 percent of Americans favored the decision to use military force. While today most of us decry the fact that no (or more accurately very little) weapons of mass destruction (WMDs) were found, a Harris interactive June 2003 survey found that seven in 10 Americans believed that Iraq actually had WMDs when the war began (69%). Moreover, 56 percent thought the US government had tried to present the information accurately versus 37 percent who thought the US government had deliberately exaggerated the reports of WMDs in Iraq.

In early polling after the 2003 invasion, Republicans were much more supportive than Democrats. For instance, nine in 10 Republicans backed the intervention, compared with around half of Democrats in Pew’s early polling. These partisan gaps on evaluations of the war continued as long as the war itself, though Washington Post/ABC News survey trends show that by 2004, support for the war had fallen to about half overall. By 2007 it had dropped to about a third. The partisan gaps that were apparent at the start of the war continued, but a Chicago Council Survey found that by 2014, even Republican support had plunged to a minority that agreed that the war was not worth the cost.

As part of the State Department’s work in Iraq after the invasion, I spent considerable time in Baghdad providing the Coalition Provision Authority (CPA) with polling data of everyday Iraqis and their challenges to quality of life, their sense of insecurity and safety concerns, and hopes for a new path for their country. I witnessed some of the honorable attempts by the Americans working there to help Iraqi society—and also some of the blunders in executing those efforts. At the time I was much more focused on Iraqi public opinion of the war and occupation than I was on US public opinion. In that vein, I really appreciated Brands' article because it acknowledged that US political leaders and the American public had already decided well before 2003 that Saddam Hussein and Iraq were dangerous not only to Americans, but to the world at large. As Brands notes in his review, “it was a war the United States chose in an atmosphere of great fear and imperfect information.” The 20-year cost to both the US and Iraq should convince Americans about the need for topnotch intelligence—and the funding to back it—as well as the potentially negative consequences of groupthink.

Related Content

US Foreign Policy

US Foreign Policy

Though partisan support has shifted over time, Council data show the public continues to favor active US engagement in global issues.

US Foreign Policy

US Foreign Policy

FiveThirtyEight draws on Council data in a podcast episode reflecting on the anniversary of the Iraq War.

US Foreign Policy

US Foreign Policy

"Too often, quick agreement on hard problems is a sign of dangerous groupthink," Elizabeth Shackelford writes.