Can you get rid of forever chemicals? More countries are finding out

By

In short: The U.S. and France recently added to a growing chorus of legislation attempting to regulate PFAS or “forever chemicals,” citing links to harmful health effects, including cancer. Found in household items such as nonstick cookware, water-repellent clothing, and stain-resistant fabrics, PFAS earned their “forever” nickname because of how long it takes for them to break down. While many PFAS chemicals are unregulated worldwide, more countries are acting to limit them, since they have been found in soil, water, and even people’s bloodstreams.

What are PFAS?

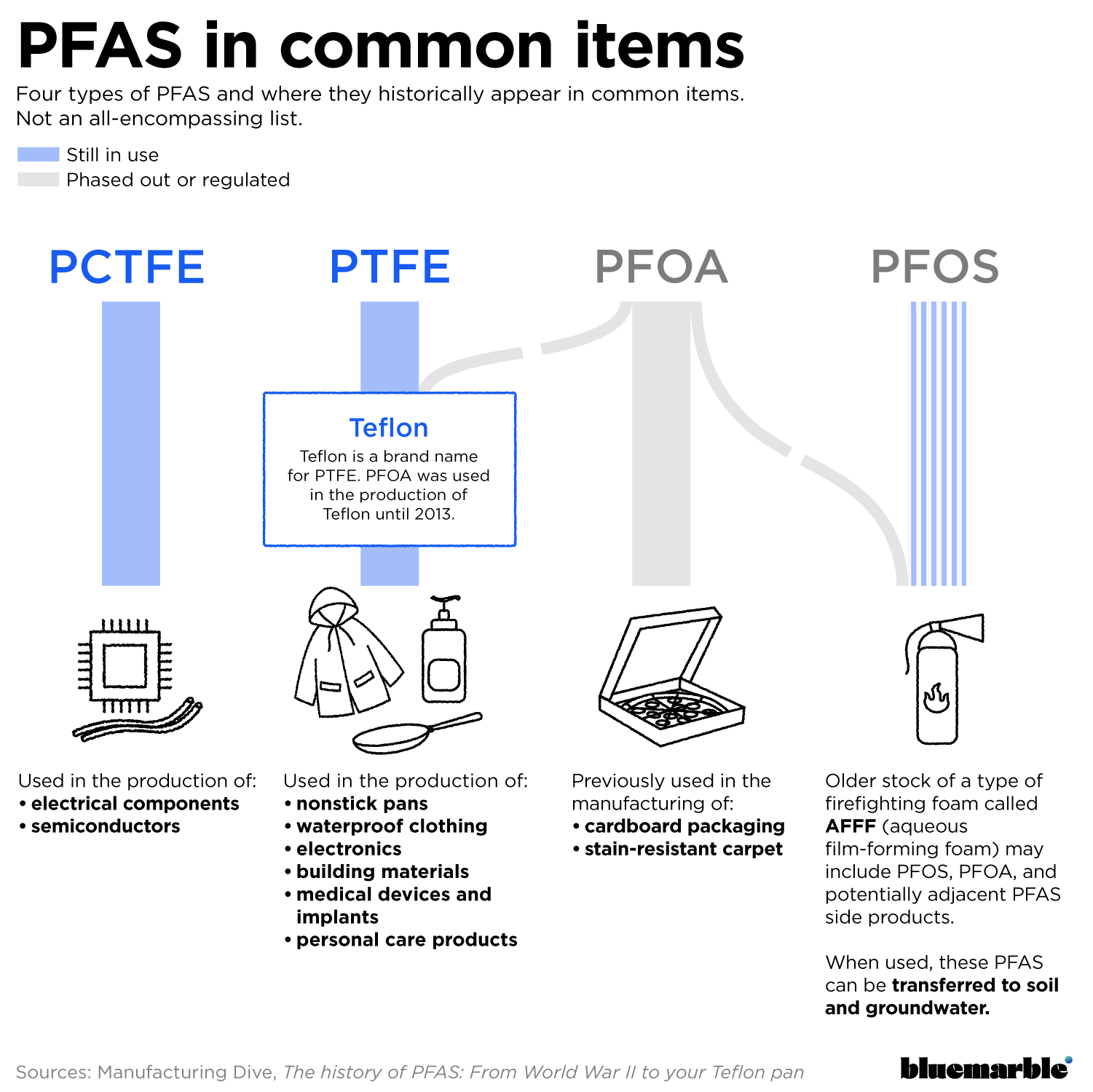

PFAS, short for perfluoroalkyl and polyfluoroalkyl substances, are man-made chemicals that can be found in everything from furniture to food packaging.

The first PFAS chemical was PCTFE, a compound created in 1934 by two German scientists. PTFE — which you may know by its commercial name, Teflon — followed in 1938. Today, though, the most researched and arguably best-known PFAS is a compound called PFOA.

Like other PFAS, PFOA is chemically resistant to water, grease, stains, oil, and heat, which, in its heyday, made it a common chemical to use in household items, including cookware, rain jackets, and cleaning products.

The properties that make PFOA and other PFAS so durable, though, also make them very difficult to break down in the body. Due to the strong bond between the compounds’ carbon and fluorine atoms, it can take over seven years for PFAS in a person’s bloodstream to reduce by half. Lead, which has been regulated since the 1970s in the U.S., takes just 32 days.

Why are countries regulating PFAS?

According to internal documents, the PFAS mass-manufacturer 3M knew at least as early as 1970 that the chemical PFOA had toxic effects in fish. Further research suggested that, by the end of the '70s, those effects had spread to humans, particularly those who worked in PFAS manufacturing. Manufacturers knew that potentially damaging PFAS were accumulating in people’s bloodstreams, but little was done to communicate that threat to the public – and by the turn of the century, the chemicals’ spread was near-universal. In 2007, a U.S. study on members of the public found PFAS in more than 98% of blood samples.

3M, DuPont, and PFAS

3M and DuPont were at the forefront of developing PFAS in the 1940s and, later, in covering up the chemicals’ harmful health effects. DuPont trademarked Teflon in 1945, and 3M was the first major commercial manufacturer of PFOA. A study in the Annals of Global Health found that both companies knew PFAS could be “highly toxic when inhaled and moderately toxic when ingested” by 1970, decades before the dangers were publicly known. Both companies have been embroiled in multiple lawsuits over PFAS, the first being a 1999 lawsuit against DuPont. In 2023, 3M agreed to pay out at least $10.3 billion in settlements.

Governments gradually started banning the chemicals as these ill effects became more widely known. PFOA, which was both highly toxic and highly susceptible to ingestion due to its popularity in cookware, was a major target of these early regulations. The European Union began regulating PFOA in 2008 and outright banned the compound in 2020. The U.S. started phasing the compound out in 2003, ultimately outlawing it in 2014. In 2020, PFOAs were banned worldwide as part of the Stockholm Convention, a global health treaty between 186 countries.

While PFOA isn’t used in commercial products anymore, the chemical is still found in the environment, and manufacturers have turned to less regulated PFAS to create the same effects.

As the chemicals continue to proliferate, an increasing number of studies have shown an association between PFAS exposure and health issues including cancer, liver damage, thyroid disease, asthma, and decreased fertility. Because of this (and despite decades of lobbying by the chemical industry), more and more countries are working to regulate the chemicals.

The Overview newsletter

The news you need to navigate our world, delivered to your inbox every weekday afternoon.

What countries are regulating PFAS?

A French law banning PFAS in almost all products except cookware passed the National Assembly on April 4, while, in the U.S., the Environmental Protection Agency set national limits on six types of PFAS in drinking water for the first time ever on April 10.

The U.S. is also subject to several other PFAS restrictions. The Toxic Substances Control Act requires manufacturers to report to the EPA on the chemicals’ production and hazards, and, at the local level, at least 28 states have implemented one or more laws regulating PFAS. In February, the Food and Drug Administration announced that, thanks to years of pressure and legislation, all American food manufacturers had stopped the use of PFAS in food packaging.

Australia has had policies regulating PFAS for at least six years, including a 2019 law requiring companies that manufacture the chemicals to evaluate potential health risks for any new types of PFAS before putting them on the market. Australian landowners have also sued their government on multiple occasions over PFAS contamination, including in a case last year where the government had to pay $132.7 million AUD (about $88 million USD) to about 30,000 landowners who argued that their land had been contaminated from PFAS used in firefighting foam on military bases.

Currently, the Australian government is in talks to propose regulations that would ban the import, manufacture, export, and use of three types of PFAS.

In February, Japan proposed regulations that would create a “tolerable daily intake” of PFAS in food and drinks – a measure that may be difficult to enforce, since some water samples in the country have been found to contain more than 700 times the proposed daily limit.

The European Union has regulated PFAS since 2008, and certain types of forever chemicals are outright banned. The organization of 27 European countries is currently considering a ban on the manufacture, sale, and use of over 10,000 different types of PFAS, albeit with exemptions meant to protect key industries.

Almost 15,000 chemical compounds are considered PFAS, and in 2018 Harvard professor Elsie Sunderland told ProPublica that, when some compounds are banned, chemical companies often just replace the old PFAS with new ones.

“People call it chemical whack-a-mole,” she said.